A ten hour drive slowly gave way to the thin sheet of dust and debris known as the Karoo.

We drove passed a herd of scraggly sheep, slowly turning yellow like the landscape they inhabited.

“I wonder if the drought has hit this part of the Karoo too,”

I pondered out loud – just in time to pass an empty river bed.

We spent a few minutes arguing whether it was a riverbed or a canyon, you and I – though I believe we both knew that in a previous life this dustpan must have been a watering hole.

Not far from the starving sheep, maybe 50 kilometres or so, the cracked earth sunk away from the mountains and gave way to the weight of the green oasis below.

Nieu-Bethesda.

A town centred on a little natural spring – one that had been supplying life to this otherwise barren desert for more than 200 years.

Nieu-Bethesda is special, not only because of its natural fountain or natural beauty, but because it once housed Helen Martins.

“You would have been her a hundred years ago,” You chuckled as we exited the car and approached ‘The Owl House’ (as Helen Martins’s old home became known).

“Me? Why me?” I recoiled.

“People would have thought you were a witch too,” You said dismissively, giving my blue hair and nose piercing a quick glance.

But Helen Martins hadn’t been a witch.

She was an artist – one who had never been recognised in her lifetime.

Helen Martins was born on December 23 of 1897 in the Karoo village of Nieu-Bethesda in the Eastern Cape.

She was the youngest of six children and spent her childhood growing up in Nieu-Bethesda.

She went on to obtain a teacher’s diploma in nearby Graaff-Reinet and, around that time, married Johannes Pienaar – a teacher, dramatist and, in later years, a politician.

Helen returned to Nieu-Bethesda in the 1930s, after her marriage had already failed, to care for her ailing and elderly parents.

Her mother, who had long been an invalid, passed away in 1941.

Her father, ‘Oom Piet’ Martins, died in 1945, and Helen was left alone, with few prospects, in this remote Karoo village.

It was some time after this, somewhere in her late forties or early fifties that ‘Miss Helen’, as she became known, was to begin to transform her surroundings.

It is certain that Helen sought praise and attention through her work but as time progressed, and derision and suspicion grew within the village, she became increasingly reclusive.

Helen was notorious for not taking care of herself and as time, arthritis, and the arduous nature of her undertaking took its toll on her physique, she became increasingly shy of her appearance and took great pains to avoid seeing people in the street.

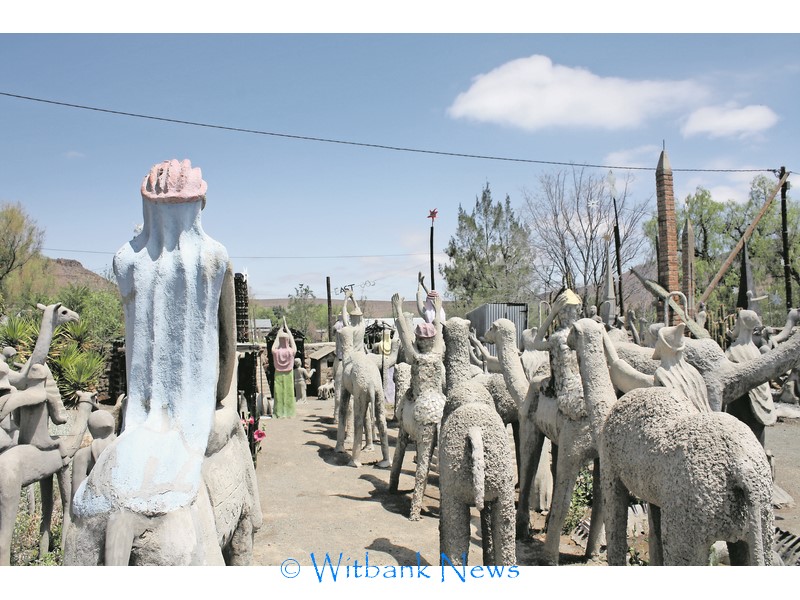

In order to pursue her vision (the garden full of statues made of cement which she had created) Helen had successfully managed to endure great physical and emotional hardship.

That is, until her eyesight began to fail her.

On a cold winters’ morning in 1976, at the age of 78, Helen Martins took her own life by swallowing caustic soda.

It was her wish that her creations be preserved as a museum.

I stood in front of one of the tall cement camels at the Owl House, a lanky man coated in coloured glass sat astride it, and my heart broke for Helen – and at the same time rejoiced.

Her dream had been realised; all who came here would surely see her artistic merits the minute they approached one of her magnificent creations. But she had died lonely.

Decrepit. Like Van Gogh and Ingrid Jonker before her, the world had simply become too much for Helen.

Helen, who could see the world in colours we could never imagine, could not find a light in the darkness.

And I wondered, why are we so cruel to artists? To anyone who dares step outside of our idea of “normal”? Are we still burning witches in the 21st century?