The Vredefort Dome is not at Vredefort — and it isn’t a visible dome. Looking for it is like seeking a ghost.

It is there, vast, impressive, and startling in its scale, but prepare to be surprised by what it is not. It is not a hole in the ground with a neat ring around it. It is not a volcano, despite early theories. And it did not rain gold from the heavens. Instead, it holds secrets that require explanation, patience, and a willingness to rethink how landscapes are made.

The gold that made South Africa wealthy was already here, locked into ancient sediments long before the impact. What the asteroid did was far more dramatic: it compressed, uplifted, overturned, and reburied those rocks in a geological instant.

Join me, Prof Graeme Addison, to see it. This is not geology you absorb from a signboard or a textbook. The Vredefort impact story only truly reveals itself when you stand inside it, trace the rocks with your hands, and learn how to read a landscape that hides its violence beneath quiet hills and rivers.

Join a guided walk or drive through the heart of the world’s greatest impact structure. Learn how to see shock, uplift, collapse, and deep time written into ordinary-looking stone — and why this place matters not just to South Africa, but to the story of the Earth itself.

The biggest blast:

The blasted truth has been reconstructed by generations of geophysicists.

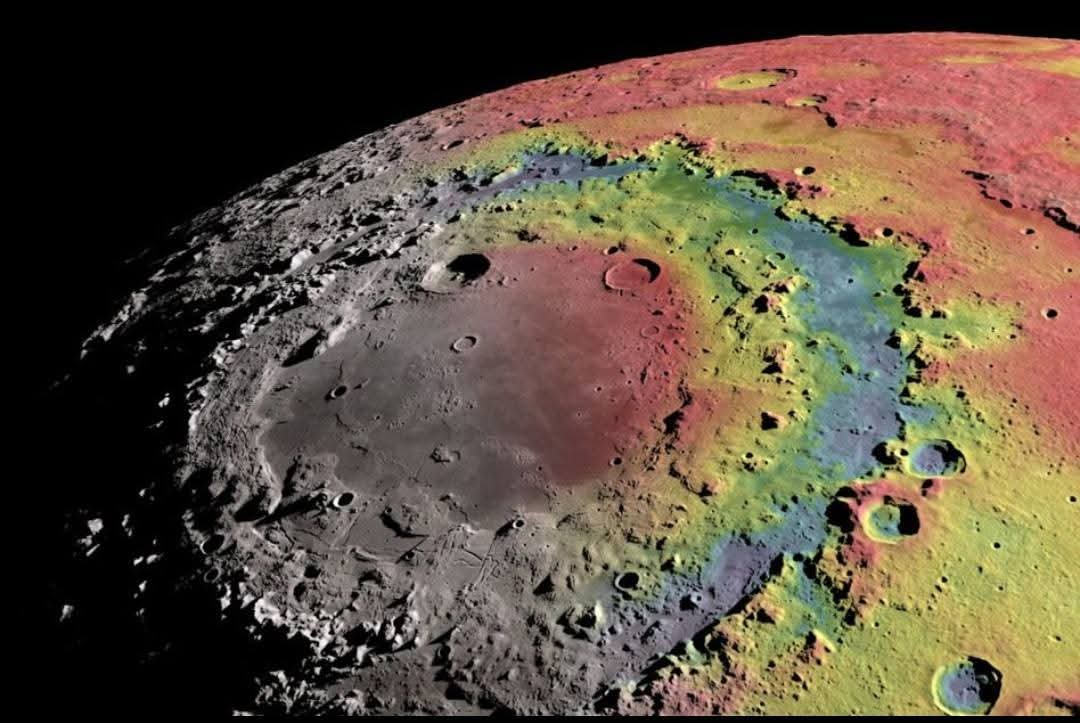

According to UNESCO, this crater represents the largest known impact event on Earth’s surface. The entire feature is the product of shock metamorphism — rock transformed by pressures and energies beyond normal tectonic processes.

Around 2 billion years ago, an asteroid roughly 10–15 km in diameter struck the early Earth here. In a matter of minutes — not millions of years — it generated forces capable of reshaping the continental crust. Mountains may have risen as high as the Himalayas, only to be erased by time. Today, the highest ridges stand barely 500 metres above the surrounding plains. What remains is a shadow — a ghost of a once colossal structure.

The immediate effects were apocalyptic. The crust was violently compressed; rocks were shattered, folded, and overturned. A vast transient cavity opened and then collapsed. There were firestorms, tsunamis across ancient seas, and debris blasted into space.

Shock waves travelled faster than rock could flow or bend — deformation occurred faster than rocks could behave plastically. This is the signature of impact, not volcanism.

Crucially, the so-called “dome” is not volcanic at all. It is rebounded crust — deep granite that was driven downward by the impact and then sprang back upward elastically. As the over-steepened walls of the crater collapsed inward, concentric ring faults and fractures formed. The original crater was immense, far larger than the feature we see today.

Long after impact:

Long after the flash of destruction had faded, the Earth was still restless.

After impact, molten rock migrated through the shattered crust. Along faults and fractures, frictional heat produced pseudotachylite — dark, glassy veins formed by instant melting during seismic slip. Under extreme pressure, melt was injected into cracks like liquid lightning frozen in stone.

These veins are one of the clearest fingerprints of impact. They tell us that the crust remained mobile, fractured, and unstable for years — perhaps centuries — after the initial event.

Long after impact, heat from the buried melt sheets drove powerful hydrothermal systems. Water circulated through the broken rocks for thousands to millions of years, altering minerals and redistributing chemistry. In an otherwise harsh early world, these warm, chemically active environments may have created niches for microbial life.

Once again, catastrophe became opportunity. The impact established long-lived thermal and chemical gradients that lingered far beyond the violence that created them.

Slow work of time:

Over millions to billions of years, the uplifted crust adjusted isostatically, gradually settling into balance. Erosion stripped away the crater rim, the melt sheet, and the sedimentary cover. Rivers planed down mountains that once rivalled the world’s highest ranges. What we are left with today is not a surface crater but its deep root — a vertical slice through Earth’s crust, exposed by unimaginable spans of erosion.

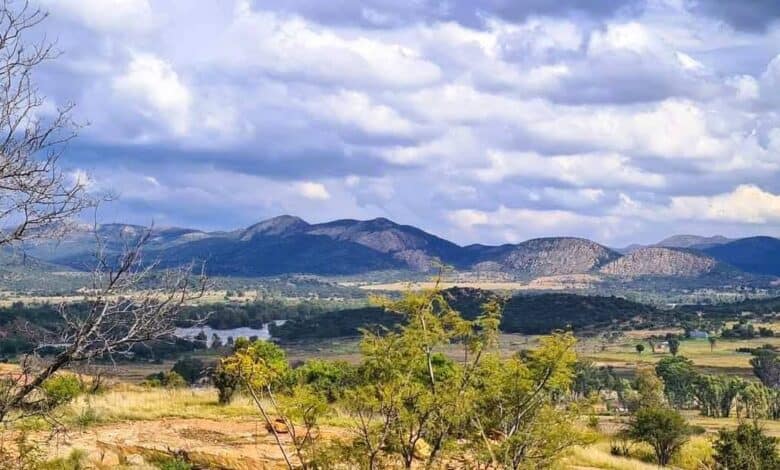

The Dome is only the central core of a much larger crater. It was first recognised in its full extent from space in the mid-1980s, when orbital photography revealed the vast circular pattern invisible from the ground. The inner core is a buried plug of granite, stretching roughly 90 km across beneath the rolling Free State landscape.

It forms a shallow, saucer-shaped basin partly encircled by ridges — the collar, or Dome Bergland.

So if you come expecting a crater with a rim, you will miss the point entirely.

This is a ghost crater. Its mountains rose in minutes and vanished over aeons. Its violence is written not in shape but in structure, not in spectacle but in stone. To understand it is to understand that Earth’s history is not always slow and gentle — sometimes it arrives in a single, world-shattering moment, and leaves behind a mystery that takes two billion years to fully reveal itself.

At Caxton, we employ humans to generate daily fresh news, not AI intervention. Happy reading!