Public participation on the Electoral Amendment Bill: Salvaging the proposal (Paid editorial)

The Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC) on Electoral Systems Reforms explored options for an electoral system and narrowed them down to two models in their report approved by Cabinet on 25 Nov 2021. Parliament’s Portfolio Committee of Home Affairs met on 7 Dec 2021 to discuss the proposed amendments and noted that the process was waiting on the State Law Advisor to provide a legal opinion, before the Minister introduces the Electoral Amendment Bill in Parliament.

A set of documents was reviewed comprising a cover letter by the Minister, the report of the MAC, a Memorandum by appointed Counsel, and a draft Electoral Amendment Bill (presumably to supplant B34-2020 that was reviewed by the MAC).

One objective of the proposed ‘slightly modified multi member constituency (MMC) option’ is to maintain proportionality utilising a proportional system as its base: MMC is commendable for starting out proportionally and consciously avoiding non-proportional systems; but it suffers from oversights that may be traced back to formal submissions and arguments devised/construed as defendable where they may not be.

The MAC report (5.1.1) proposes the introduction of ‘independent candidate’ into the definition of ‘party’. Currently the definition includes ‘registered party’ and ‘organisation or movement of a political nature’, which are constructs at ‘grouping level’ where a ‘catch-all-grouping’ may fit in seamlessly to partition the broader political choice landscape correctly – into mutually exclusive and exhaustive ‘representation avenues’ when registered. The definition is from another Act (51 of 1996) and not addressed in the draft Bill, which does provide a definition for ‘independent candidate’ and a nomination process confining independents to ‘regions’ – suggesting that the ‘party’ definition may not change. Nonetheless: Political ‘choice’ used to imply ‘party’, but as ‘choice’ expands to include ‘persons’ the definition of ‘party’ and its context needs an overhaul to a more generic term such as ‘grouping’ to avoid confusion when it includes for example: party, organisation, movement, ‘apparentement’, ‘list of independent candidates’ (as defined), and, for any/all unaccommodated nominated candidates a ‘catch-all avenue’ (redundant potentially, but not trivial).

The MMC by design tolerates ‘wasted’ votes exclusively for independents. Less obvious is the source of unequal vote value/weight embedded in the procedure of the Memorandum (23), similar to the source causing the deviation that ‘came to 3.5%’ in 2019 mentioned in the MAC report (5.1.2) that precipitates as non-proportionality: the presence of avoidable sources of inequality in the MMC procures 50% of 400 seats to compensate non-independents exclusively, on the premise of correcting for proportionality without a non-proportional system present. Delegates are persons and could logically be party members or independents: what is lacking for independents is a recognised ‘grouping’ or ‘representation avenue’ included in the (amended) ‘party’ definition, duly harmonised with other pieces of legislation. The interpretation of ‘in general’ may fall short.

Recent electoral system amendment efforts are best spared being torn into as the proposal is salvageable by starting a process that utilizes the MMC as a base and that steers its useful components towards compliance with the court ruling, while consciously achieving meaningful improvements for the 2024 elections. Limited numbers of people are positioned for this rather intricate ask – mature leadership will be important while fragilities require careful handling if success is to be achieved:

A: Defuse a point of contestation (perhaps yet to surface) and acknowledge that multiple votes introduce complexity too easily blown out of proportion, ruling out desirable voting systems relying on it: accept that single votes will be cast for the 2024 elections, as MMC proposes. Furthermore: (i) Focus on the principle that in any proportional system the only contest is the popularity contest resolved by votes (whether cast at individual level or grouping level or mixed) – the procedures of the system exist purely for allocating the number of available seats to reflect that vote. (ii) Address other key principles in concert with the voting system, not necessarily as part of it, as it is generally accepted that voting systems have a purpose, importantly, within a broader democratic context. (iii) When appropriate, stress the point that multiple votes, if anything, supports broad acceptability and may aid certain key principles.

B: For the National Assembly election, the MMC might be mended by abolishing compensatory seats and altering the procedure of the Memorandum (23.1 through 23.3) as follows: with votes counted, determine the proportion cast for independents; ignore the quota and, of the 400 available seats, calculate the corresponding number of seats reserved for independents; rank independents across constituencies on one list according to their vote count (creating a ‘party’ list) and from the top allocate the correct number of seats. Re-join the Memorandum’s (23.4) procedure to allocate seats to parties for the remaining number of seats. The modification achieves proportionality specifically for independents and specifically for parties – a significant improvement for equality; but, as for any class-creating distinction – from which the MAC report (5.2) second model and its type characteristically suffers – bound to be bespoke, troublesome, and inferior to meeting a requirement ‘as a rule for all cases’ or (in that sense) ‘in general’. Therefore:

C: Find an equivalent to South Africa’s List Proportional Representation system designed to accommodate voting at the individual level. One such option is described at https://www.citizen.co.za/potchefstroom-herald/shop-local/electoral/ halfway through the article: It relies on the assumption that a single vote at individual level is explicitly afforded a run-off vote contained within the associated grouping for the technique to be the equivalent of a single vote at the grouping level (that implicitly includes the same assumption). It is proportional in of itself. Allow experts in the field, across interested parties, to verify the claim, to be prepared if called as expert witnesses, and to guide the transition from the current MMC to a redressed version, which combines the current system with its equivalent for voting at individual level. Retain components of the MMC that do not need fixing, such as the filling of seats becoming vacant between elections, and tolerate provinces as constituencies (fewer constituencies reduce difficulties) as permitted by ballot paper sizes (manageability may gain prominence): allow the governing party to propose refinements to these including stipulating reasonable ballot list lengths. Such a redressed version (equally and without incentive) accommodates this hypothetical quandary wherein independents claim to be also a ‘blanket movement for direct representation’ and register a ‘party’ allowed a self-fielded open list ranked by voters for its ‘party’ list purposes: the MMC exhibits no comparable robustness.

D: As a stand-alone matter, or, given open ballots for persons to be directly elected (that MMC concurs with), test the fairness of parties being constrained to the closed list, as MMC seems to imply, unable to field party candidates on the same open ballot next to independent candidates to break their induced monopoly on direct representation. If affirmative, allow parties to choose one or the other: the closed format as MMC proposes, or the augmented open format for fielding candidates for the electorate to decide their fate directly (rendering party lists preferred, not required). A party’s seat allocations should be the same whether the vote tally is aggregated via the closed format (a vote for a party directly) or the open format (a vote counted as if for a party through its association with fielded candidates). Arguably all ills of the MMC in failing to ensure equality will be exposed when adding fielded party candidates to the open list, allowing efforts to shift from dismantling towards redressing the MMC to henceforth treat independent candidates equally to fielded party members, and parties equally in their choice of format. Arguments for and against equal treatment will be in the public domain and potential election campaign source material.

The envisaged redressed MMC is predictably simple, robust, equivalent to the current, fit for purpose, and no-one’s favourite. It remains to be seen whether all parties voluntarily opt for the open list format – 2024 may be sanative.

Thomas R Labuschagne

Considerations for South Africa’s Electoral ReformsThe inherent trouble with a Mixed Member Proportional system in the context of South Africa’s electoral reforms is that by considering it one implicitly assumes that it is going to be necessary to deviate from Proportionality before correcting for it again. Any correction later-on will be smaller or negligible if one does not insist on deviating from it to start out with. South Africans have been allocating votes proportionately for a while now and we should utilise that know-how for our benefit. |

Different voting systems are in use in different countries around the world. South Africa’s is due to be amended following a Constitutional Court ruling, and proposals will likely take into account some features of other systems. Three features of voting systems: Proportionality, Connectedness and Voter Choice, are important in this context.

Elements of these three features are referenced in the South African Constitution: its Founding Provisions Section 1 mentions accountability and responsiveness, which is generally associated with Connectedness and should benefit the public if it is improved upon (although not specifically required by the court ruling). Section 1 also prescribes a multi-party system, or Voter Choice between at least two options available on the ballot paper; for provincial and national elections Voter Choice now needs to improve by incorporating independent candidates. Sections 46, 105 and 157 are clear on Proportionality that is to be maintained, which narrows the scope of the required reforms.

Volumes of literature exist to guide one’s understanding of issues: South Africa in 1995 became a member of the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance who in conjunction with other organisations in 1998 at the United Nations launched The ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, an online community and repository of electoral knowledge available at the address https://aceproject.org/, the main source of information used herein.

One person one vote principle

Even with limited knowledge on voting systems, valuable insights can be gained by having certain basic questions answered satisfactorily. Basic question 1: Does each voter have a single vote across all voting systems in use? If so, then one may presume that, per election/round, a voter is allowed to tick one box only, typically using an ‘X’. Had someone made more than one tick, that vote is void; if you spoil your vote it is rejected. Yet this matter could have been handled differently by splitting the weight of the voter’s single vote equally to as many boxes as were ticked – equally since no information is available about the voter’s preferences: were three ticks made instead of one, then a third of a vote goes to each candidate selected. Fractional votes remain meaningful but arguably less so the more boxes are ticked until when all boxes are ticked it becomes as meaningful as a tick for an only box (with Voter Choice severely constrained) and no contribution towards selecting between candidates registered. Conversely, approving of more candidates than there are seats available keeps the vote meaningful where some chosen may be eliminated early. An ‘Allow Fractional Votes’ amendment requires a change to the manner in which representatives are elected, and to the Electoral Formula, one of Three Key Concepts of voting systems. The objective of such an amendment, amongst others, may be to reduce inadvertently spoiled votes in more complicated systems. It is clear though that fractional votes add up to the original weight of one vote that all voters have, and it does not result in cheating.

The answer to the first basic question reveals that a single vote may not be the core issue: at its core is whether a voter’s vote ‘carries the same weight’ as everyone else’s in all components of the voting system, considered here as equivalent to the principle of one-person-one-vote; if it does it is fair to voters. Fairness is satisfied in many different types of voting system and gains relevance where amendments are proposed: should a component of a new design or an amendment fails to maintain equal weights for votes, then it should be rejected if not revised to fix the error.

The electorate is being talked about. Voters, it is postulated by some, may find certain voting techniques too much to comprehend while others say no, it shouldn’t. What is your view – if you vote in elections and are used to casting a single vote, will you be ‘as able’ to cast say three votes for three different persons? You may, of course, select all three from one party if that is your preference, or you may use one vote for a candidate of another grouping, or all three for different independent candidates – it is up to you how to use them if you believe you can handle multiple votes and voting. What about ordering your top three candidates with the number ‘1’ for your favourite choice, ‘2’ for your next favourite, then ‘3’? If this is not overwhelming, then both multiple votes and ranked preferences could significantly enhance the features of a voting system – it certainly is a matter worthwhile considering.

Types of Voting System

The Borda Count, devised in 1770, requires of voters not to tick a box but to rank the candidates and ‘put them in a queue’ using integer numbers starting at 1 for the preferred candidate up to as many candidates are listed. The Ballot Structure (second of Three Key Concepts) determines whether a voter votes for a candidate or a party, and whether a single choice is made or a series of preferences expressed. For Borda Count the vote is for candidates at the individual level; every box gets a number and the ranked queue provides all the information necessary for the system to take over and for algorithms to ensure meaningful selection between candidates. A crude example of such an algorithm is for the system to apply the reverse order of someone’s ranked queue as ‘points’ (e.g. 1 point for your least favourite up to maximum points for your most favourite, closely similar to how it was done originally), then to add up the points across all votes cast and determine the highest ‘points-based’ score achieved in the election.

Interestingly, Borda Count achieves ‘broadly acceptable’ outcomes in that it may be possible for a candidate that happens to be more voters’ second or third choice to score highest and beat the biggest contingent’s number one; it occurs because the single vote cast is spread out in a predetermined manner across candidates, based on the information provided in voters’ ranked queues. The Supplementary Vote system does not require ranked numbers (rare for the broad group of preferential voting systems that it forms part of) and it has a very different Electoral Formula to Borda Count, and while it does not in the same sense disperse a vote across candidates, the possibility of a run-off count that it offers, results in candidates campaigning to secure a broader base of support.

First Past the Post is a well-known voting system with a long history where the candidate on the ballot paper receiving the most votes is elected the winner irrespective of whether it reflects the majority’s vote or not; the results for the ‘First Few’ Past the Post may be readily available too if needed (as in multi member districts, then referred to as a Block Vote system). Every additional candidate in the running creates more Voter Choice but reduces the likelihood of the majority electing the winner, creating a trade-off between two features both desired but not both satisfied. Invariably, without a way out, voters may choose to move their support away from their favourite to an acceptable candidate with a greater chance of winning against another lowly preferred candidate. Tactical voting is better handled by design. If it is consecutively applied, First Past the Post resembles the Two Round system that is ‘First-and-Second’ Past the Post in its first round, which satisfies Voter Choice, then after the top two candidates are determined, for them it becomes First Past the Post in round two with the winner elected by the majority.

Ideally a single election should determine the winner, which is at odds with multiple compounding of rounds needed to gradually whittle down the candidate list; in such a multiple round scenario, a voter whose preferred candidate was eliminated, either stops voting or votes for the preferred candidate on the next reduced candidate list, and again in the next round, repetitively. The Alternative Vote system requires of voters to vote for their favourite candidate using integer number ‘1’ and either stop there or to also select their next favourite using ‘2’, then ‘3’ and so forth for as many or as few as they wish to order in this manner, in effect sourcing all information for multiple compounding on a single ballot paper, at which point the system takes over: the lowest scoring candidate is eliminated and all the affected ballot papers distributed to the next preferred candidates, if one was provided. The process is repeated until one candidate achieves the majority vote and is elected, and in this manner, the Alternative Vote system in a single round of elections deals with the characteristic issue of vote splitting under First Past the Post.

Ranked data and voting systems theory

Ranked data provides a lot of information. A typical example from voting systems theory is used to compare select voting systems and illustrate the interest that exist in attempting to improve on existing systems: Three candidates are in a close race for a single seat of office (president, mayor, etc.) – votes have been cast, counted and reported in decreasing order – candidate A (37%), followed by B (33%) and C (30%) adding up to 100%, of course.

In a First Past the Post system, A wins without securing a majority. In an Alternative Vote system, C is eliminated and it turns out that, of the 30% of voters who voted for C at least 18% favours B over A as their second choice (and at most 12% the other way around), which is enough for B to win with a majority vote (51% = 33% + 18%) in the head-to-head contest with A. Pairwise head-to-head contests is what the Condorcet method is all about; if it turned out that C is a broadly accepted candidate amongst voters and secured at least 21% second preferences from the 37% in the camp who voted for A on top of another at least 21% second preferences from the 33% in the camp who voted for B, then the Condorcet method would have declared C the winner, beating both A and B in head-to-head contests, suggesting that C is merely unlucky to be eliminated early. For Borda Count, more information is needed to decide the winner, but broad acceptability would reflect in the weighted score, points-based or otherwise, and increase the chances of C achieving the highest weighted score to win in a single round and single count without elimination.

Many factors need to align for dilemmas of voting systems theory to play out in practice, but they are useful to highlight the inner workings of systems.

Comparing/contrasting voting systems

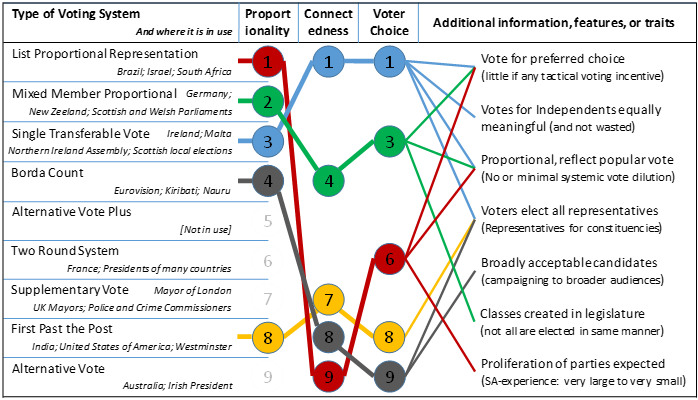

South Africa’s List Proportional Representation system (where voters vote for a political party), together with the Mixed Member Proportional system (also known as Additional Member System) and the Single Transferable Vote, are systems that have been designed with the aim of being more proportional. Much of the information reproduced predominantly in this section is sourced from the Electoral Reform Society in the UK, at https://www.electoral-reform.org.uk/ who, for nine types of voting system, as a rough guide, provide rankings on each of Proportionality, Connectedness, and Voter Choice, which are incorporated into Figure 1, a rich picture also incorporating additional information and own interpretations; some names were changed to align with conventions used in the main source.

Figure 1: Proportionality, Connectedness, and Voter Choice rankings.

The voting systems are listed according to the Proportionality ranking. Start with a particular system on the left, use its colour coding and follow it to the right to find rankings on each of the features. First Past the Post (colour: gold) ranks lowly (8) for Proportionality and for Connectedness (7) and Voter Choice (8), suggesting that other systems fare better. By comparison Borda Count (colour: grey) ranks fine for Proportionality (4) but lower than First Past the Post for Connectedness (8) and Voter Choice (9). Other typical features are found by following the colour coded lines further to the right, with some of the traits mentioned there shared amongst different systems.

The three systems designed to achieve Proportionality occupies the top three spots (red, green and blue) on the Proportionality ranking. Move to Connectedness and the order in which they appear reverses (blue, green, and red) and spreads out across the column; they remain in that order for Voter Choice where their rankings improve again.

List Proportional Representation (colour: red) is top for Proportionality (1) but bottom for Connectedness (9) as voters do not directly elect representatives in the closed list format but vote at the grouping level. A grouping does not formally exist for ‘independents’ and one (that is not a party) may need to be provided, particularly should List Proportional Representation be used in combination with another system to correct for Proportionality. Another option is simply to ‘open the list’ and let the electorate directly elect representatives off the ballot paper that lists all candidates running independently and being fielded by parties, improving on both Voter Choice and Connectedness.

Mixed Member Proportional (colour: green) combines List Proportional Representation (red) and First Past the Post (gold) and its mid position (between blue and red) in the rankings may be expected. The Proportionality ranking (2) is much higher than the rough midpoint between red (1) and gold (8), which is no coincidence as the proportional system is included by design to correct for Proportionality (if it does not then the combination is referred to as a Parallel System instead). The non-proportional system in the combination will be relied upon to accommodate independent candidates and is used in the combination to elect individual candidates directly for a predetermined proportion of total seats available, with the remainder ‘correctively elected’ using the Proportional Representation system. The combination of systems carries the risk of creating classes of representatives in the legislature. Too big a set proportion for the non-proportionally elected class may not allow enough space for corrective election of the other class to achieve Proportionality. The extent of partitioning in the district structure could aggravate this risk, but, as long as it is not breached, the combination should share the top spot on the Proportionality ranking.

The Single Transferable Vote system (colour: blue) achieves Proportionality through its Electoral Formula and vote counting methods. In a multi-member constituency, a party may have enough support to get two candidates elected but if one candidate is very popular and pulls excess votes away from the other, then, in another type of system, the popular one may (comfortably) get elected at the expense of the other not being elected – only that will not happen here: when a candidate reaches enough votes to gain a seat, the Single Transferable Vote system will transfer excess votes for that candidate to the next preferred candidate as indicated by voters, resolving half the challenge of excess votes for popular candidates for parties, who are left with the challenge of not fielding unpopular candidates who may then not receive the excess votes. At the bottom end (as for the Alternative Vote system) the lowest scoring candidate is eliminated and affected votes are transferred to the next preferred candidate, allowing voters to vote for their favourite not having to worry about wasting their vote. Single Transferable Vote achieves top rankings in Connectedness (1) and Voter Choice (1). It is the one system adjudicated to treat independent candidates equitably.

Democratically elected representatives

The 1994 elections ushered in a new era of inclusivity for South Africa that did not exist before. Voters voted for political parties as was probably necessary at the time. To this day Members of Parliament remain not directly elected but are put forward by parties as a collective for voters to ratify through their votes at grouping level. It may need to be ascertained whether this intermediation is intended: at stake is whether a seat of parliament should ‘belong’ to a grouping with a possible consequence of incentivising ‘pyramid politics’ not necessarily representative of the people of the country, or whether it should ‘belong’ to the person put directly into office by the electorate as a representative, with increased Connectedness achieved. It is assumed here that voting at the grouping level was initially necessary to achieve Proportionality, for it to be a straightforward decision to change to an ‘open list’ system for the electorate to directly elect all members of parliament on the same basis whether they are fielded party members or independent candidates that are not fielded.

Each individual candidate could be associated with a specific grouping. Therefore, a vote for a particular person can unambiguously be linked to a particular grouping as long as the association between a grouping and its members is clear, and since this is possible it is also sensible to avoid voting at the grouping level as it would create irreconcilable feedback loops. Arguments that persist for voting at the grouping level should be aired – ‘Democratic elections, after all, are not a fight for survival but a competition to serve’ (the electorate and people of the country and no special subset thereof) https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/gov/democracy-elections.htm (more is taken from this source below). Opening the closed list should have no bearing on party processes to decide which members to field – it should remain as big a milestone for political parties to follow ‘most democratic processes’ in that regard, and on top of it having the candidates fielded also democratically and directly elected to the legislature. Party lists remain important (also for tie-breaking purposes) and should continue to be submitted in advance.

Proportionality and how to measure it

Proportionality in the outcome of an election, or the lack thereof, is relevant at the grouping level (not the individual level where popularity matters). Distinguishing between the levels is important: If 20% of voters voted for candidates fielded by PartyX and 10% for independent candidates (not fielded), then, in a proportional system, at the grouping level, voters will expect to see 20% of seats allocated to PartyX and 10% to Independents (the grouping); if not close enough, then something is the matter with the supposedly proportional voting system.

Where non-Proportionality exists, the ‘popular vote’ usually features in discussions. The popularity measure utilised here is Votes Received, the aggregate of valid votes cast in the election for a particular grouping. Another important measure is Votes Allocated to a particular grouping, which is the ratio of Seats Won to total seats available applied to the Total valid Votes (TvV) in the election; the terms are rearranged and it is calculated in two steps first by defining the Full Quota (FQ = TvV/S), the number of Total valid Votes divided by the number of seats (S) available – same as the Hare Quota not rounded, then multiplying Full Quota by Seats Won to equal Votes Allocated, which is fine as a fraction (not an integer). Votes Allocated conveys to a particular grouping its ‘worth expressed in votes from the perspective of the system’ or its share of the total valid votes that it may claim to represent by occupying seats.

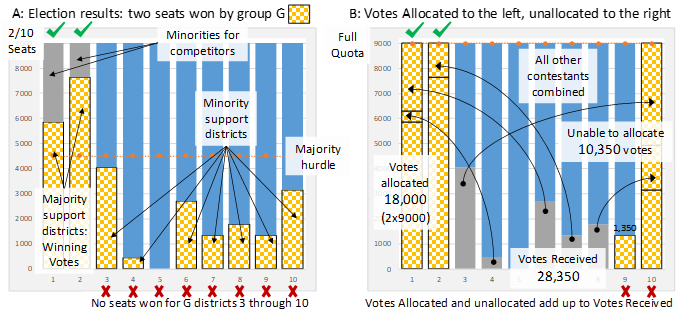

For example, if 90,000 valid votes are cast across many candidates contesting for 10 seats then a Full Quota is 9,000 (90,000 votes divided by 10 seats). If a grouping G that fielded candidates secured two seats with counts of 5,850 and 7,650 for 13,500 combined Winning Votes, and also secured support in other districts totalling 14,850 Losing Votes, illustrated in Figure 2A, then its tally is Winning Votes + Losing Votes = 28,350 Votes Received, illustrated in Figure 2B where votes for G are allocated to its Seats Won by filling up Full Quotas, with residual votes moved to the right to arbitrary seats that are filled up sequentially until all votes for G is orderly rearranged in this manner. No vote is ‘lost’ in the process that could have had a bearing on non-proportionality. Group G received enough votes to fill another Full Quota and non-Proportionality is evident in the voting system used to achieve the results.

Figure 2: Election results and votes allocation

The Surplus-of-Votes (–10,350) is defined as Votes Allocated (18,000) less Votes Received (28,350), the latter being the ‘worth expressed in votes from the perspective of the voting public’. If the Surplus-of-Votes is zero then exact Proportionality is achieved. Every vote by which it deviates from zero causes bigger non-Proportionality, negative (a deficit) if the particular grouping suffered from non-proportionality and positive (a surplus) if it gained from it. A measurable deviation from a zero Surplus-of-Votes exposes a discrepancy between two differing concepts of ‘worth expressed in votes’ – in the example of Group G, a significant deficit of representation given its popular support.

The magnitude of the Surplus-of-Votes at some point becomes too significant to tolerate; when it exceeds a Full Quota as in the example above, then correction-for-Proportionality by design allocates additional seats to any grouping that suffered from non-Proportionality – one seat to be corrected for in the case of Group G above. Where it is smaller than the Full Quota (like after correction for Proportionality), the Surplus-of-Votes of a particular Group relative to that of other groupings becomes important. Select a useful denominator, such as Full Quota (9,000) and use Surplus-of-Votes (–10,350) after being corrected (by +9,000), as the numerator (–1,350) divided by the denominator (9,000) to express the Surplus Ratio (–15.0%) as a percentage. The Surplus Ratio is equivalent to the Hare Largest Remainder and is utilised for allocating seats shared amongst different contestants to some of them.

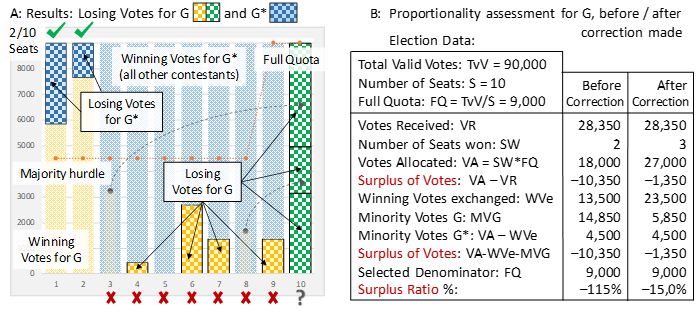

The Surplus-of-Votes could be expressed differently. Elementary mathematics is necessary to derive it: the seats that Group G won outright (Figure 3A below) is where Winning Votes for G were cast, which together with Losing Votes cast for G*, the compliment of G, being all its competitors, makes up Full Quotas. As a consequence, Votes Allocated for G less Winning Votes for G equals Losing Votes for G* its competitors (in checkered blue) that is of specific interest here and won’t be rearranged as was done before. Conversely, in each of the other districts, Winning Votes for G* all its competitors plus Losing Votes for G (prior to being rearranged) combines to fill Full Quotas and it is clear that Votes Received for G less the (same) Winning Votes for G equals the Losing Votes for G (in checkered yellow) of which some has been moved to the right to fill up a Full Quota (in checkered green) as it was done earlier. Add and subtract ‘Winning Votes for G’ in the definition Surplus-of-Votes: Votes Allocated less Winning Votes G less Votes Received plus Winning Votes G, and it is clear that the definition is in fact not changed but new terminology for it is introduced, to become: Surplus-of-Votes (also) equals Losing Votes G* less Losing Votes G.

Figure 3: Losing Votes; Proportionality assessments

When correcting for Proportionality, a Full Quota of votes, the green bar Figure 3A, is ‘exchanged’ for a seat. Losing Votes for G* (in checkered blue) is unaffected, but Losing Votes for G decreases to the residual (in checkered yellow) after moving out the green Full Quota that increases Votes Allocated by the same amount; the Full Quota exchanged becomes part of Winning Votes exchanged (or Surplus-of-Votes will have two distinct values which it can’t).

Differences in Winning Votes exchanged for seats between proportional and non-proportional voting systems hinge on the ‘hurdle to pass’ or the level of the quota that needs to be reached to become elected: the highest vote tally determines this level for plurality systems where no run-off information is required, unlike for both majority systems where the hurdle to pass is 50% and for proportional systems where it is a Full Quota, that do require sufficient run-off information to boost more popular candidates’ tallies by eliminating less popular candidates from the count.

Proposed counting options for Proportionality

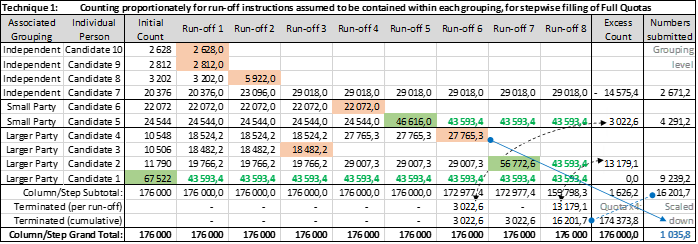

Divisor-based counting methods exist but are not considered here; instead, quota-deduction based methods are utilised for proportional counting: the Hagenbach-Bischoff quota is the theoretical lower limit (the biggest number too small) for a quota; South Africa uses the Droop quota, an integer value marginally bigger; the Full Quota (Hare quota, not rounded) is however the preferred quota utilised herein. The example used next is from South Africa’s 2019 national elections: if 17 437 379 valid votes were cast for 400 seats, then for that election the Full Quota is 43 593.4475 not rounded; it will be rare for it to be an integer. A Full Quota is to be filled (reached or breached) by enough votes received in order to get elected proportionally at individual level. For Proportionality to be achieved, it is not the most votes nor the majority of votes that matter, but filling Full Quotas.

With the Full Quota set, the focus shifts to a hypothetical multi-member voting district where 176 000 valid votes were cast: it is divided by the Full Quota to determine the District Seat Fraction (4.037…) that is split into a truncated integer part (4) the number of seats to be allocated locally, and a residual fraction (0.037… not rounded) transferred for aggregation at the ultimate level. Both parts are multiplied by a Full Quota to yield (174 393.79) Votes Allocated at district level and (1 626.21) Surplus District Votes to be allocated at the ultimate level.

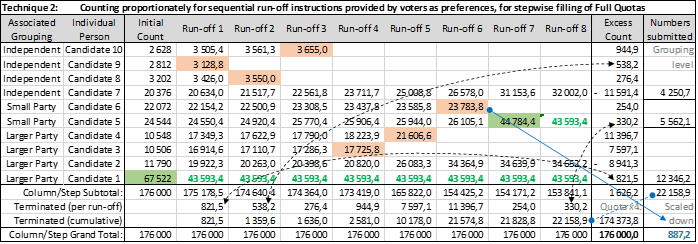

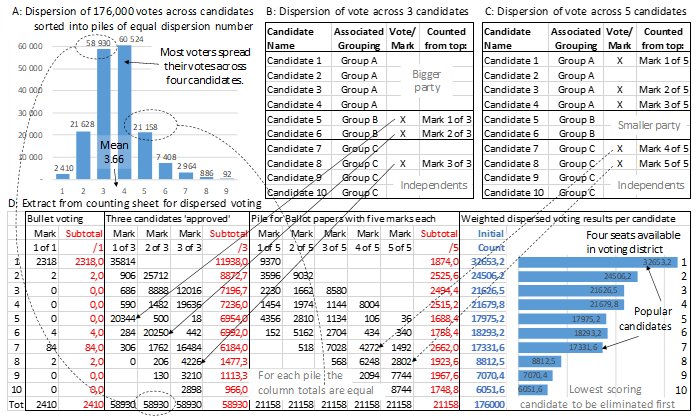

Ten candidates are contesting the election, four of whom are fielded by a bigger party, two more fielded by a smaller party, and four are independent candidates. One set of election results was modelled for three different counting techniques. The techniques assessed below are suitable for voting at the individual level for seats to be allocated to the person voted into office by the electorate. The techniques differ: one requires single votes and relies on an assumption for stepwise elimination, while the other two source the elimination information from voters and require multiple votes.

In all cases an initial count is performed, followed by a stepwise elimination process: as soon as the Full Quota is breached at any step in the process (initial or run-off) the particular candidate is elected; if more than one breaches the quota simultaneously, they are elected one-by-one starting with the highest tally received to keep the process orderly; if no-one breaches the quota at a particular step, the lowest scoring candidate is eliminated.

1. Counting proportionally for single votes

Results for this technique are illustrated in Figure 4 below. One tally (67 522) breaches the Full Quota at the initial count: Candidate_1 is elected with excess votes (23 928.5525) determined and recycled into the count. An important assumption is made: excess votes for a representative elect is retained within the associated grouping by splitting it equally amongst candidates of the same associated grouping still in the running. The influx of recycled excess votes does not get another elected. At Run-off 1, two are eliminated (as no votes will terminate and exit the count yet). At Run-off 6 Candidate_5 breaches the quota and is elected; no candidate remains in the running for the small party to receive the excess votes, however, and in the next step the lowest scoring candidate is eliminated with that tally transferred to Candidate_2 who breaches the quota and is elected in Run-off 7; calculations for excess votes are completed. With one seat available and one candidate left to be allocated it, the process stops. Two seats go to the bigger party, one to the smaller party, and one to an independent; one more remains in the running for seats allocated at ultimate level – Candidate_4 is the last to be eliminated at a tally of (27 765.3) scaled down to (1 035.8).

Figure 4: Single votes counted proportionally

Excess votes that could not be recycled exit the count at the bottom of each run-off column and are also recorded in the row of the candidate that contributed the number; the final cumulative terminated votes number becomes the subtotal of the ‘Numbers submitted’ column, where each individual number submitted is calculated as a Full Quota added to each excess count number (for each of four elected) scaled down by the final cumulative terminated votes number divided by the grand total. The subtotal (1 626.21) of the Excess Count column reconciles with the Surplus District Votes defined above if counted correctly: it is the voting district’s contribution to additional seats available at ultimate level; added to Votes Allocated (174 373.79) it agrees with the grand totals at the bottom; divide it by a Full Quota to scale down the maximum tally for the last to be eliminated (bottom right corner).

The technique is uncomplicated and requires little additional effort beyond the initial count. It achieves voting at the individual level and seamless integration and equal treatment of independent candidates and candidates fielded by parties on a single ballot paper. It offers geographical representation that closed List Proportional Representation does not. It results in representatives democratically and directly put into office by the electorate. It maintains Proportionality by never deviating from it. These are all potential benefits from simply opening the closed list and utilising voting districts to manage ballot paper sizes.

2. Counting proportionally for ranked preferences

For the second technique the initial count is a carbon copy of the first, but run-offs differ: the run-off assumption is dropped for ranked preferences provided by voters. The results differ as illustrated in Figure 5: the same four candidates are elected at district level as before but the last to be eliminated here is Candidate_6 who remains in the running with a scaled down tally of (887.2).

Figure 5: Run-off instructions counted proportionally

Candidate_1 is elected at the initial count as before, exits the count, and is ‘removed’ from all votes by shifting up all lower ranked candidates on a particular vote to occupy the space left vacant (best performed electronically). All the votes for the representative elect (not only an excess) are redistributed to their newly updated first ranked choices, but are kept separate next to the initial count column to keep matters orderly and for a weight to be applied to them to scale down the tally (67 522) to the value (23 928.5525) of excess votes, before being added to the tallies of the candidates receiving the run-offs. The value of a Full Quota is retained in the row to reconcile the column count for Run-off 1, where lowest scoring Candidate_9 is eliminated, exits the count, and is ‘removed’ from all affected votes as before. Votes available from an elimination, are recycled at their prevailing (unadjusted) weights.

Unlike the former technique, at each step here votes are being terminated as voters preferred not to provide further run-off instructions, which is their prerogative: (2318) bullet votes were cast for Candidate_1 and the (821.46) terminated reflects the effect of downscaling the recycled votes to surplus vote values, with the residual left behind in the Full Quota meaningful in getting a representative elected. Terminated votes are copied to the Excess Count column on the right, and remain meaningful by influencing the outcome of excess seat allocations at the ultimate level. More terminated votes accumulate in this technique compared to the former, and only two representatives elect breached the quota; the other two elected at district level will have their Full Quotas filled at ultimate level.

The parallels of this technique with the Single Transferable Vote system and its enhancements proposed over time (Gregory method; Meek’s and Warren’s methods; the Wright system) may be evident.

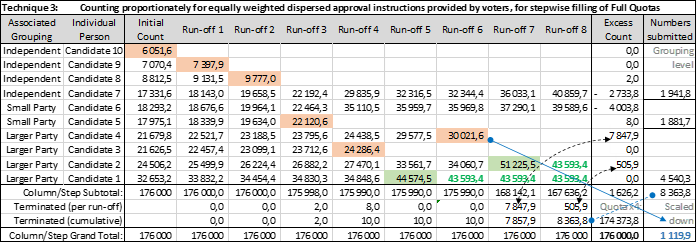

3. Counting proportionally for dispersed approval

Dispersed approval voting is multiple votes (ticks or crosses) that carry the same weight in the absence of numerical ordering; the weights are fractions, determined by the extent of dispersion across candidates. The third technique is applied to the same data set and changes the initial count as each mark made needs to be taken into account (not only the first/only preference). The counting process involves a lot of repetitive counting. In preparation for the count, all votes are separated into piles according to the ‘width-of-dispersion’ of votes across candidates: a pile for single (bullet) votes, another for two marks made, then three, and so forth as illustrated in part A of Figure 6. A particular pile is chosen and its votes are counted starting with the uppermost mark on the ballot paper (parts B and C Figure 6) with the count recorded in the appropriate space on the counting sheet (extracts of which are shown in part D of Figure 6); followed by another count for the next mark made, and the next, until ‘n-of-n’ marks were counted for the particular pile, before moving to the next pile and repeating the process. An orderly arrangement supports the verification process: column totals on the counting sheet should be equal and correspond to the total votes of each pile of a specific width-of-dispersion.

Figure 6: Data for votes cast for dispersed approval

A weight is applied to the vote count per pile as illustrated in the columns in red font in Figure 6 part D: It requires division by the ‘width-of-dispersion’ number, which ensures that dispersed votes are fractionally weighed to add up to one vote. As before, the column total for the weighted count (in red) equals the other column totals of the same pile. For the final step in the initial count all weighted dispersed votes per candidate are aggregated across the piles for the initial vote count result (in blue font) and corresponding chart. Multiple votes and the repeated counts associated with it, increases the counting effort considerably; while it can be done manually, it is advisable for data to be electronically captured as part of this initial manual count to aid in the processes that follow.

Dispersion reduces the effect of bullet voting in multiple voting systems, and unlike previous techniques, no-one is elected at the initial count. Results are illustrated in Figure 7 below. Stepwise elimination or election is performed as it was done for the other techniques. The other candidate of the small party is elected, and Candidate_4 is again the last to be eliminated in this count, this time scaled down to (1119.9).

Figure 7: Dispersed approvals counted proportionally

Candidate_10 with the lowest initial dispersed count is eliminated first: all votes that has a mark for that candidate are found (easily searched for in an electronic database) for the candidate to be removed from it, leaving the vote spread across one less remaining candidates. Since the width-of-dispersion reduces, the vote is moved to a pile with a corresponding width-of-dispersion (and a higher fractional weight). After all the affected votes are updated and moved to a neighbouring pile, another count is performed on the same basis as the initial count, only with one candidate less. The lowest scoring candidate in the run-off is eliminated and the process repeated. At Run-off 5, Candidate_1 breaches the quota and is elected, with excess votes (all votes scaled down as before) dispersed to remaining candidates sharing in a dispersed vote with the representative elect. Another elimination occurs at Run-off 6 resulting in another election at Run-off 7 where the process stops.

For this technique the votes exiting the count are lower than any other. Neither of the first two candidates eliminated received bullet votes (Part D Figure 6) but for Candidate_8 eliminated in Run-off 2 two bullet votes were cast ending up in the count for terminated votes for Run-off 3 and copied to the Excess Count column. Increments in tallies are generally more subdued for this technique, as are fluctuations in the excess count.

Sequentially Proportional to complete the count

There are two distinct types of count in the complete process: One type of proportional count at district level where votes are counted adhering to voter instructions to fill Full Quotas, for which the second and third techniques are well suited; either may be used, but preferably both to afford voters the choice of ranking candidates or approving equally of multiple ones they select. The change in level causes proceedings to pause that is useful to check for deviation or to verify results before final allocations are made. The other type of proportional count is at ultimate level where submitted information are aggregated across districts and allocated, confined within groupings, to maintain proportionality. The first technique is suitable for the task but a quicker First Few Past the Post system applied within contained groupings, is sufficient at the ultimate level, where two key activities are performed:

The first key activity is to allocate votes to the shortfalls of those candidates elected at district level without breaching the quota; numbers submitted per grouping are aggregated across districts creating a pool of votes for each grouping from which shortfalls are filled, leaving less in the pool for the affected groupings for seat allocations to follow. The subtotal of the Excess count column increased by the shortfalls of candidates elected without breaching the quota to become the higher subtotal of the Numbers submitted column above, and, after deductions made here, reduces again to the Surplus District Votes numbers aggregated across districts, to be allocated next.

The second key activity is to allocate the correct number of seats to the deserving last to be eliminated at district level candidates still in the running. Exactly enough votes are left in the pools of votes available to fill Full Quotas. Each last to be eliminated candidate’s highest count achieved, as scaled down (multiplying it by the Surplus District Votes divided by a Full Quota), determines that candidate’s ranking within a particular grouping, as if a closed list is compiled. Residual votes pooled at grouping level are allocated in Full Quotas starting at the top ranked candidate in the grouping, each time electing a representative, until fewer than a Full Quota is left. It is done for all groupings, leaving unallocated residuals still to be allocated: The Hare largest remainder or Surplus Ratio is used to decide which candidates across groupings are deserving of the remaining seats to complete the process.

The data submitted to the ultimate level is reflective of the end result of the allocation process at district level. It is proportional, but what has been called a ‘barrier of entry’ created by district partitioning affects smaller groupings more severely: with Independents a recognised grouping this should not affect them as badly and may incentivise members of very small parties rather to run as independents to benefit from the larger grouping.

Ballot structure and ballot paper

Ballot papers have a typical format. The link between a candidate receiving the vote and the associated grouping needs to be clear, listing candidates in blocks, one grouping after the other top to bottom, with candidates sorted alphabetically within each block. If lowly populated neighbouring voting districts would have been merged, then it becomes a single district to which the same basic ballot paper layout will apply; if not merged but merely sharing a ballot paper, then within each political grouping candidates are split between the districts, with the district name clearly indicated next to each name.

Leniency towards spoiled votes is important in multiple voting systems, and effort should be put into interpreting the markings on the ballot paper for rules to be devised accordingly: If integer numbers are offered as markings by a voter then the vote should be interpreted as a run-off instruction, except if all numbers offered are equal, in which case it may be interpreted as dispersed approval vote. Votes should not be transferred from one type of count to the other – once within one type of count it should stay there. If markings other than integer numbers are made (ticks; crosses) then they are interpreted as equally ranked dispersed approval votes. Both types of multiple vote counting techniques are needed to keep spoiled votes to a minimum, and as an early step in the counting process votes should be sorted according to the technique that will be used to count them.

Tie-breaking mechanisms are needed. For dispersed approval counting the dispersion and its fractional votes makes it much less likely that ties between candidates will occur: should it happen nonetheless then a run-off may be temporarily performed by eliminating one and record how many votes the other receives in the run-off, then to reset and temporarily eliminate the other – the one who ends up with the lowest temporary run-off tally is to be eliminated, and the main process is reset and proceeds. For ranked preference counting more elaborate tie-breaking mechanisms may be needed: Any ‘difficult to interpret’ vote due to equal ranking may be temporarily held back to allow correctly cast ones to be counted first at a particular step of the process. The temporary candidate tallies (as yet only for correctly cast votes) is then applied as the tie-breaker and for each vote with equally ranked candidates the vote goes first to the candidate with the highest temporary tally, which may not exist if temporary tallies happen to include a tie too (very unlikely, but possible): In that case, same as earlier, a temporary count is performed with one eliminated first, reset, and a temporary count performed with the other eliminated, to determine which is the more deserving candidate and break the tie, for the main process to proceed again. Ranked closed lists submitted in advance by groupings may be used to break a tie between candidates fielded by a particular grouping. More tie-breakers may exist to help postpone declaring a vote spoiled.

For multiple votes a rule may be devised that each voter has ‘at least two’ votes and may cast as many as preferred but not less than two, or if insisting on a bullet vote then in full knowledge that the single vote cast carries half the weight of others conforming to the rule. The objective being to incentivise multiple votes and penalize bullet voting that quickly result in terminated votes exiting the count.

Potential future electoral reforms

For South Africans, political choice is not limited to political parties. One future reform possibility may be related to the current requirement not to exclude independents: should independents not be recognised as a grouping for whom Proportionality at grouping level may have to be corrected for, then the next logical reform required is to allow independents ‘apparentement’ https://aceproject.org/ace-en/topics/es/esd/esd02/esd02e/esd02e04 to organise themselves into a recognised grouping that is not a party but for whom Proportionality needs to be achieved as for every other grouping. This possible future reform is also aimed at small parties who may find it even more difficult to gain seats in a partitioned constituency based system. Allowing any contestants to form recognised groupings counters the effect of the unintended ‘barrier of entry’ created by district partitioning.

Not all valid political choice is formalised: the possibility of deliberately spoiling a vote has been publicly propagated and discussed in the media where it is recognised that blunt instruments of democracy may have only limited value https://www.ru.ac.za/german/latestnews/archive/spoiltvotesarebluntinstrumentofdemocracy.html like a formalised ‘none-of-the-above’ option on the ballot paper would likely suffer from too: intended messages may be interpreted any other way. Compatibility with a ballot paper is also an issue: a spoiled vote spoils any valid vote made with it, and in a multiple voting system it would be nonsensical to use one of the votes to select a candidate and another for ‘none-of-the-above’. The article considers tactical voting to be a more effective course of action. A need for tactical voting (like a need for voting with your feet in another direction as the voting station) is symptomatic of not having a way out of a predicament – and that it comes with unintended outcomes, concurs with the view that tactical voting is better handled by design.

The possibility of formalising the vacant seat option needs to be approached carefully: it is an option that could logically share in a multiple vote with other choices on a ballot paper, and result in a proportional number of seats elected vacant, reducing Members of Parliament’s aggregate remuneration bill and requiring closer cooperation amongst representatives who have been elected to achieve a threshold in a vote, as the messages conveyed. Since in democracies the authority of the government derives solely from the consent of the governed and since periodically elected representatives do accept the risk of being voted out of office, and since it is not out of the ordinary for voters to express discontent at the ballot box through tactical voting for an alternative with tangible results, formalising the vacant seat option is deemed here akin to allowing for tactical voting by design. That it may be used ‘spitefully’ (either my choices or vacant) is a bigger concern, but even if that becomes the norm for voting (adding a ‘last in the queue’ vote for a vacant seat to the modelled data) its impact under normal circumstances will be that few votes (if not none) terminate at each run-off to exit the count – and in all techniques described earlier cumulative terminated votes are not enough to fill a Full Quota and no seat would have been elected vacant for those examples.

Options to reverse the incentive to vote for a vacant seat may include: formalising the public participation process to give more weight to objections by the public; extending elections beyond only selecting representatives; devising rules to incentivise multiple votes; interpreting a vote for a vacant seat as either the lowest ranked preference, or dormant until all other approvals are eliminated. Options to contain its impact may include setting a limit on its reach such as one vacant seat per multi member voting district, taking into account any ranges set for the number of seats available in the legislature and/or absentee numbers for perspective https://www.polity.org.za/article/absentee-mps-should-be-sent-packing—anc-2016-10-12 .

To formalise them will likely require court rulings, and potential future reforms are not given further attention.

Partitioning of Electoral Districts

‘Constituency’ and ‘voting district’ are deemed synonyms for the Electoral District, the third of Three Key Concepts of voting systems. The default district structure for First Past the Post (and its rival Alternative Vote) systems is to have constituencies across the country equal in number to seats in the legislature; it is the fully partitioned structure and results in good geographical representation in the legislature and keeps ballot papers manageable. At the other end is the non-partitioned structure, a single country-wide voting district as found in Israel and the Netherlands, with geographical representation likely lost (and in all likelihood voting at the grouping level a practical consideration to keep the ballot paper manageable). In countries like Finland and Spain provinces are used as voting districts that are few in number with a big group of representatives each – a partially (lightly to moderately) partitioned structure.

Partitioning results in mutually exclusive voting districts (voters registered with one are not registered with another) and exhaustive (there are no left-over voters without a constituency). Basic question 2: Assuming that voting district boundaries are not redrawn regularly and that migration patterns constantly alter populations, can a constituency based structure with voting at individual level ensure that all votes cast ‘carry the same weight’ in an election?

Voter-to-representatives ratios across the country’s voting districts are affected by district population sizes. Conventional wisdom suggests that it is easier to achieve votes carrying the same weight in lightly-to-moderately partitioned structures where larger groups or teams represent a district because in larger groups the effect of removing or adding one representative to control for the relevant ratios as populations change is much subtler compared to the other end of heavily-to-fully partitioned structures where it is going to be all but subtle to add or remove a representative. The type of voting system being used may have a bearing on the issue too.

There is another take on the matter as applicable to proportional voting systems: strictly, it is actual (valid) votes cast that must carry the same weight in the election. The ratio for the number of valid votes per available seat is defined above as the Full Quota. The requirement then for having votes carrying the same weight across Electoral Districts is properly met my determining the Full Quota at the ultimate level once, and to apply it to all Electoral Districts, however populous they are and however well or not their voters turn up on election day. The total number of seats will still be allocated, but the actual number of representatives per Electoral District is finalised only as part of the counting process in the same manner as it is done for groupings contesting the election. Finalising district seat/representative numbers as an election outcome is different to how things are done currently and requires an administrative change. It remains necessary to plan in advance, as too lightly populated a district may end up with no representative, which will be correct and defendable especially if exasperated by low voter turnout in the affected district, but nonetheless potentially embarrassing. Groupings who are fielding candidates will have to adapt their strategies: published information such as for numbers of registered voters per district will remain useful.

For provincial elections being held simultaneously with national elections it is important that the provincial level is considered the ultimate level for the provincial election, with each province determining its own Full Quota to be applied to all voting districts within its boundaries. For simultaneous national elections the Full Quota at national level is applied to all voting districts in the country. Each voting district conducts and counts for two elections being held simultaneously – one provincial with a provincial quota and the other national with a national quota. No voting district that is a subset of the region conducting an election applies its own quota: it applies the quota relevant to the region conducting the election. The concept may be extended to municipal level too.

District partitioning is closely linked to geography, but the need to partition also stems from a practical consideration to keep ballot papers manageable and not have too many candidates listed in any constituency. Including the eight Metropoles, there are 52 District Municipalities across South Africa, that may be considered as suitable multi member constituencies for provincial and national elections. A few are sparsely populated, notably Central Karoo and others in the Northern Cape, that may require attention. The remainder are populous enough to serve as decent sized multi-member constituencies with some Metropolitan Municipalities very populous resulting in significantly more representatives for them, which should be fine in principle, but is a matter for someone else to decide on.

Lowly populated districts may not necessarily have to be merged if the ballot paper can simply be shared with a neighbouring district, allowing voters of both districts to vote for candidates in the neighbouring district, no different to a merged district, particularly with multiple run-off votes available. The main requirement will be for the district name to be clearly associated with each individual candidate contesting for a seat in it (as it is done for a grouping) for representation to be restricted to local representatives for the local district, if of course elected as such: voters may still choose to elect only representatives of a neighbouring district (as if the districts are merged) if they prefer.

Consensus amongst interested parties

There certainly is public interest in South Africa’s electoral reforms and at least three proposals have been made, one of which is covering three options. With some differing views on the best way forward, and presumably not all views tabled yet, it might be prudent to formulate points on which there is consensus across different proposals and interested parties, and in doing so highlighting matters causing differences of opinion, for the motivations behind those to be publicly aired and for the matters to be addressed in the interest of the South African public.

Points on which consensus amongst interested parties (or debate) would be welcomed based on the perspectives described herein:

- Votes cast need to carry equal weight throughout the inner workings of voting systems, and importantly, it is also actual votes cast that need to carry equal weight across all demarcated electoral districts in an election.

- Proportionality is relevant at the grouping level, not at the individual level (where popularity matters).

- The word ‘Independents’ is accepted/recognised as the grouping for all independent candidates contesting elections, or a grouping (that is not a party) needs to be created for this purpose to exist in legislation, to automatically qualify for elections, and where required to be proportionately corrected for in vote counts.

- Voting at grouping level should be abolished: votes at the grouping level assume that run-off or dispersion instructions are confined to a grouping but instead the electorate should determine whether that is the case by being offered run-off and dispersion choice. All voting should occur at individual level, and through their association with a (single) grouping, any relevant aggregation at grouping level may be performed.

- Seats of parliament (not elected vacant) are owned by persons being the representatives elect, requiring by-elections should any that was allocated to a person becomes vacant. No intermediary should own the seat.

- The requirements of the Constitutional Court ruling can be met without amendments to the Constitution.

- Multiple voting, through the run-off and/or dispersion options it makes available, if anything, is expected to benefit broadly acceptable contestants whether of their own accord, or through their association with broadly acceptable groupings.

The efforts of the New Nation Movement in initiating South Africa’s current electoral reform process is acknowledged in closing, as is the effort of all who strive to bring the matter to a constructive close.

Thomas R Labuschagne