The future path of US interest rates is unclear, while in South Africa patience will be required, as the transition to structurally lower inflation will take time.

Traditionally, central banks have been thought of as staid, conservative institutions, while most people found monetary policy, to be frank, a very boring topic. However, not anymore.

The billionaire Murdoch family – inspiration for the hit TV series Succession – recently announced a deal that effectively ended its own succession battle, with eldest son Lachlan taking over control of News Corp and Fox. [Given the unfolding central bank drama], perhaps the next boardroom TV saga will be set in the US Federal Reserve’s (Fed) headquarters.

Just days before last week’s scheduled meeting of its monetary policy body, the Federal Open Market Committee, it was still unclear who would attend. Governor Lisa Cook was fired by President Trump for allegedly being dishonest on a mortgage application, but she challenged the dismissal, and a court ruled that she must remain in her role for now.

Meanwhile, the Senate confirmation process was rushed to get Stephen Miran, a Trump advisor, on the board just in time for him to vote. Trump has been pushing aggressively for the Fed to lower borrowing costs. In the end, the drama was unnecessary: Cook joined the rest of the committee in voting for a 25-basis-point rate cut, while Miran voted for a 50-basis-point reduction.

Trump has since applied to the Supreme Court to remove Cook. It seems unlikely that this appeal will succeed, but if it does, other Fed officials could also face removal. Regardless, Fed chair Jerome Powell’s term expires in May, and the race to replace him could be one of the most consequential in recent history.

ALSO READ: Reserve Bank keeps repo rate unchanged at 7%

Fed’s 25 bp cut

The 25-basis-point reduction in the federal funds rate was expected and means the Fed joins many other central banks in resuming its cutting cycle. The bigger question is how far and how deep this cycle will go. It will have implications for investors all over the world, since the Fed is still the most important central bank.

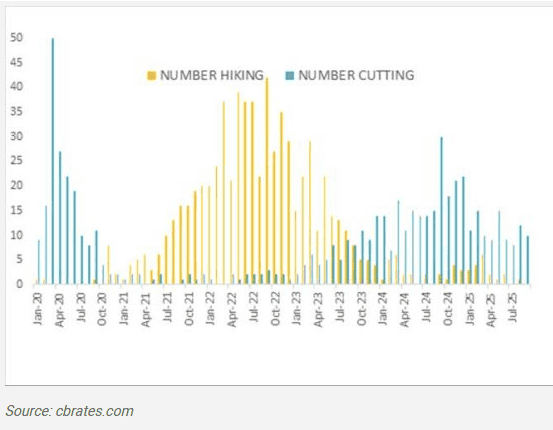

Chart 1: Number of central banks cutting or hiking each month

Central banks can lower interest rates for good or bad reasons. A ‘good’ cut would be when inflation is falling or expected to fall, meaning high interest rates are no longer needed. This is sometimes characterised as a “soft landing”, since the economy did not buckle under the weight of high interest rates and can now benefit from lower borrowing costs. This scenario is normally beneficial to bond and equity markets.

A ‘bad’ reason, by contrast, is when the economy is headed for recession and requires emergency support. Such emergency rate cuts would help bonds but usually not equities, as investors would worry about the impact of a recession on profits.

Indeed, equity bear markets usually coincide with recessions.

ALSO READ: Repo rate unchanged as economists expected

If we take recent US interest rate cycles, as an example, the 2019 pivot was a ‘good’ cut, while the plunge in rates in 2020 was ‘bad’ since it was a response to the Covid-19 economic shutdown. The 2024 reductions fall into the good camp again, since inflation had come way down, while the economy remained resilient – a soft landing.

Last week’s rate cut falls in between, making it less straightforward to interpret. Even Powell acknowledged this in the press conference, noting that it’s “challenging to know what to do.” Part of the problem is that the Fed, unlike most other central banks, has a dual mandate: stable prices and maximum employment. These twin objectives are pulling in different directions.

Inflation has been rising recently, moving away from the 2% target. Some of this is due to import tariffs and is likely to be once off. However, there are signs of sticky inflation in areas where tariffs should have no direct impact, such as non-housing services. The last thing the Fed wants to see is unaffected companies raising prices and blaming it on tariffs.

ALSO READ: Economists’ expectations for inflation and the repo rate this week

Moderating growth

On the other hand, economic growth has moderated and job creation is stalling. This too is partly tariff related, with the massive uncertainty around trade policies probably resulting in firms postponing hiring decisions. Companies could also be experimenting with artificial intelligence to see if they can get away with not adding staff.

The unemployment rate remains low at 4.5%; however, this is partly due to the fact that labour supply has shrunk, with more than one million immigrant workers leaving the workforce since the start of the year.

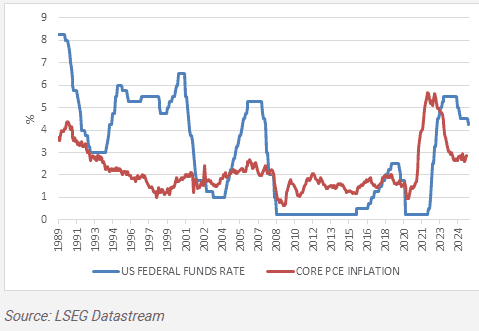

Chart 2: US interest rates and inflation

Powell therefore characterised the decision as “risk-management,” since the Fed believes it is more likely that unemployment will rise than that inflation will run away. This sounds about right. If the labour market keeps cooling, it should pull inflation lower. However, this doesn’t tell the full story.

If the economy remains resilient, the risk of rising inflation cannot be completely ignored. Clearly, ‘risk management’ in this context is also about managing political fallout.

ALSO READ: Reserve Bank cuts repo rate despite US Fed decision

Keeping rates unchanged would invite further attacks from the Trump administration, yet taking any political considerations into account, even for reasons of self-preservation, is a slippery slope.

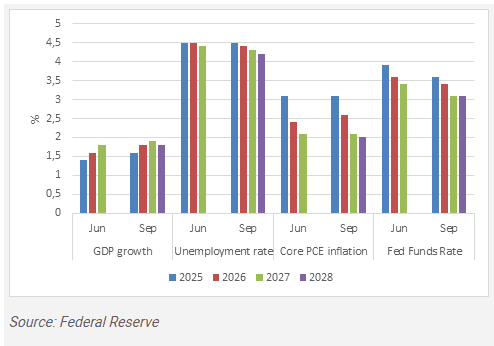

And while the rate cut was mostly a consensus decision, there is disagreement on the path ahead. The quarterly summary of economic projections from the seven Fed governors and 12 regional bank presidents – informally known as the dot plot’ – is the closest thing we have to a base-case scenario. The median projection from each summary is shown in chart 3 and compared with the previous quarter (no 2028 forecasts were available at the June meeting, however).

Chart 3: The Fed’s summary of economic projections

US inflation is expected to average above slightly 3% this year, falling back towards 2% by 2027. The unemployment rate is not projected to rise, despite worsening labour market conditions. A slightly better GDP growth outcome for 2025 is now pencilled in, reflecting ongoing solid consumer spending and a smaller tariff impact, as the effective tariff rate is not quite as bad as the headline numbers due to various carve-outs, exemptions, and ways of circumventing.

ALSO READ: Inflation still low enough for repo rate cut, but only in September – economists

The median forecast for the fed funds rate, shown on the right of chart 4, is what the market fixates on, pointing to two further 25-basis-point cuts this year. However, this hides the disagreement on views on the committee.

One member, presumably Miran, sees rates falling to as low as 3% by the end of the year, while another member favoured a hike. The range for next year is between roughly 2.5% (six 25-basis-point cuts in total) or staying put at 4%.

In a nutshell, the future path of US interest rates is unclear. Inflationary pressures could halt the cutting cycle prematurely, while political interference – especially after Powell’s replacement comes on board – could accelerate it. A recession would lead to rates tumbling. The in-between scenario of a gradual easing seems most likely at this stage, which should be good for the stock market and the bond market at the shorter end of the curve, but negative for the dollar.

ALSO READ: Surprise that all MPC members were in favour of repo rate cut

No drama in SA

Closer to home, the South African Reserve Bank (Sarb) does not face the same upheaval and uncertainty. All members of the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) are Reserve Bank staff, which may lead to groupthink, but avoids political drama. Every now and then there are rumblings of nationalising the bank, one of the few worldwide still privately owned. Private ownership is not a guarantee of good policy, just as public ownership does not necessarily lead to bad policies.

The main thing is that the bank will continue to be able to make independent, evidence-based decisions in the long-term interest of the economy – a freedom that is enshrined in the Constitution.

Independence clearly doesn’t guarantee that the Sarb will always make the right decision, but it does give it an ability to take a longer-term view and do unpopular but necessary things.

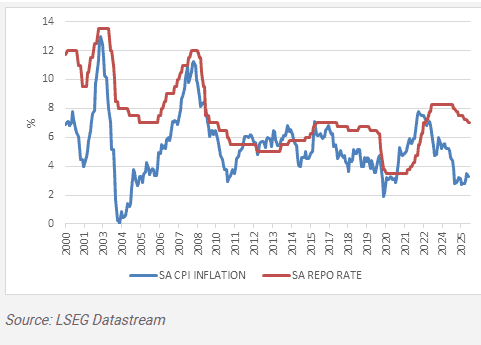

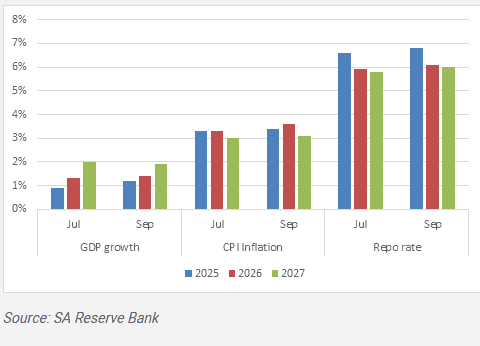

Chart 4: South African inflation and interest rates

The MPC recently decided to aim for the lower end of its 3% to 6% range. National Treasury must still formally change the inflation target to 3%, but the MPC’s focus has already shifted, and informed the decision to keep the repo rate unchanged at 7%.

Two of the seven members preferred to cut rates, suggesting that the MPC won’t necessarily be dogmatic as it transitions to the lower target. For instance, the MPC statement noted that it wanted to see how the 125 basis points of rate cuts over the past year are affecting the economy.

ALSO READ: Reserve Bank cuts repo rate thanks to lower inflation, stronger rand

So far, inflation remains low. Consumer inflation, based on the official consumer price index, declined unexpectedly to 3.3% year-on-year in August. This was mainly due to a surprise dip in food inflation. Core inflation, which excludes food and fuel prices, rose to 3.1%. There are other useful indicators such as producer inflation (1.5% in July) and the retail sales deflator (2%). The broadest measure is the GDP deflator, but it has the drawback of being only released quarterly. It was only 1.4% in the second quarter.

In response to this experience of lower inflation, inflation expectations, as measured by the Bureau for Economic Research, declined further in the third quarter. Participants now expect inflation to average 4.1% over the next five years, the lowest since the start of the survey in 2011.

This is important since the Sarb wants people to get used to the idea of lower inflation, such that it starts impacting their behaviour. The more businesses, consumers, and workers believe that inflation will be 3%, the more likely inflation is to converge on 3%.

The Reserve Bank’s own forecasts suggest that this is not impossible. It expects inflation to average 3.4% this year and 3.6% next year, before declining to 3% in 2027. The projection includes the recently updated and increased electricity tariffs, which the MPC lambasted as highlighting the “serious dysfunction in administered prices, which undermines purchasing power and weakens growth.”

Chart 5: South African Reserve Bank forecasts

The Sarb’s forecast model also produces a projection of where the repo rate is likely to be, given the growth and inflation outlook. The MPC always stresses that this model forecast of the repo rate is only a guide, and that rate decisions will always be based on the data as it arrives.

ALSO READ: Only one more repo rate cut expected in 2025 thanks to Trump policies – economists

Nonetheless, the model suggests that up to 100 basis points in cuts are possible if things proceed as expected and confidence grows that inflation is likely to trend towards 3%. The extent to which the Fed cuts rates will be a key factor.

The more it reduces rates, the more likely the dollar is to decline, opening room for other central banks to ease.

Although further repo rate cuts are unlikely this year, things could look different next year. Despite the impressive performance of the bond market this year, real interest rates remain high across the yield curve. Some patience will be required, as the transition to structurally lower inflation won’t happen overnight. But, when lower interest rates eventually arrive, they will undoubtedly be good for the local economy and local financial markets.

Izak Odendaal is an investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth.

This article was republished from Moneyweb. Read the original here.

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.