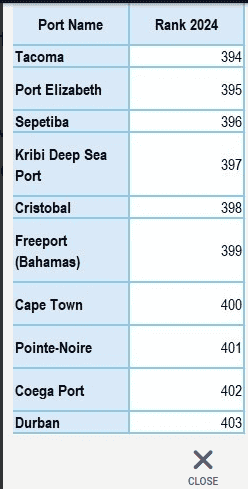

With Coega, Cape Town and Port Elizabeth also in the bottom 10 of 403 ports.

The Port of Durban ranks dead last in the World Bank Container Port Index for 2024, released on Tuesday (23 September), with Coega coming in second last out of 403 ports worldwide.

Cape Town is only marginally better, ranking 400th – just ahead of Point Noire in Republic of Congo – with Port Elizabeth at 395. This means four of South Africa’s busiest ports are ranked among the worst in the world, continuing the trend highlighted in the 2023 World Bank report.

What’s different this year is that Durban has slipped from 399th (out of 405 ports measured) in 2023 to 405th.

Last year, Cape Town was in last place, so has edged up slightly to 400th.

Port Elizabeth was in 404th position in 2023, moving up to 395th in 2024.

Bottom 10: Container Port Performance Index (Graph 1)

Source: World Bank CPPI and S&P Global Market Intelligence, and Moneyweb

The latest report will no doubt cause consternation at Transnet, which last year criticised the World Bank’s findings as “marred by factual errors” that did not accurately reflect port performance.

One criticism of last year’s report was its narrow focus vessel turnaround times without accounting for external factors such as extreme weather, operational challenges and supply chain disruptions.

This year’s report notes that the Container Port Performance Index (CPPI) measures time spent in container ports, strictly based on quantitative data without reference to the underlying factors or root causes of extended port times.

ALSO READ: Cape Town port ranked the worst in the world

Transnet will take some consolation from the fact that Cape Town and Coega were listed as among the most improved ports between 2023 and 2024. There are undoubted signs of progress not yet reflected in the World Bank study, with Liebherr and Transnet Port Terminals recently concluding a 10-year partnership agreement to modernise SA’s ports.

The Port of Cape Town recently took delivery of the first instalment of 28 cranes, also supplied by Liebherr, contributing to a marked improvement in port throughput in recent weeks.

The index is produced by the World Bank and S&P Global Market Intelligence and offers a global benchmark for container port efficiency using consistent, verified, and empirical data.

This year, the World Bank report attempted to soften the findings by avoiding including a table showing the worst performers, so we had to reconstruct the data as shown in Graph 1 above.

Of the 20 best performers, 10 are in China and two (Port Said in Egypt and Tanger-Med in Morocco) are in Africa.

The report also highlights the most improved ports in the world since 2020, but SA is nowhere to be seen on this list. Posorja, Ecuador; Gothenburg, Sweden; and Marseille, France, were the three most improved ports.

ALSO READ: Court decision delays revamp of Durban container port

The report, entitled The Container Port Performance Index (CPPI) 2020 to 2024: Trends and Lessons Learned, includes a multi-year analysis showing port performance over time.

The CPPI measures the time container ships spend in port, which is a critical point of reference for port users and the broader global economy.

“The aim of the CPPI is to provide an objective measure of container port performance, identify global or local trends in maritime container trade efficiency, and highlight where vessel time in port could be improved,” says the World Bank.

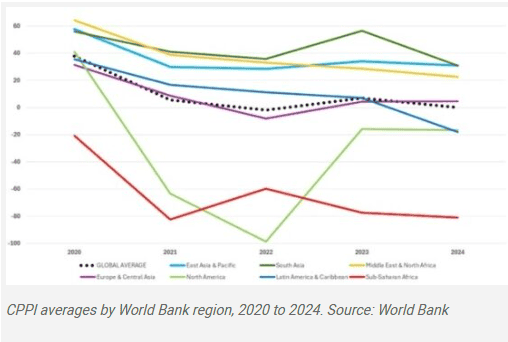

Over the last five years, the CPPI has proven to be a reliable mirror of the stresses and recoveries observed across global supply chains. In 2020, port performance started strong but the Covid disruptions from March saw a marked deterioration in port performance due to congestion, vessel delays and equipment shortages.

Ports in high-income economies regained much of their pre-Covid operational efficiency in 2023, but there was a partial reversal in 2024 caused by conflict in the Red Sea and the rerouting of vessels around the Cape, as well as climate-related disruptions at the Panama Canal.

ALSO READ: No resolution to container handling crisis at Durban port

“Sub-Saharan Africa faces persistent structural challenges, including limited automation and weaker hinterland connectivity,” says the report.

“The Red Sea crisis added further strain in 2024, notably reducing performance in ports such as Durban and Cape Town, already under pressure from longer vessel waiting times,” the report adds.

“The CPPI of Durban and Cape Town is significantly affected by longer arrival times, such as waiting times at anchor, while the time at berth has not changed substantially between 2023 and 2024,” it says.

However, Transnet Group CEO Michelle Phillips said in a recent results media briefing that waiting times for container ships at Durban and other ports are a thing of the past.

Dakar in Senegal recorded one of the largest efficiency gains in sub-Saharan Africa. It has been operated by DP World since 2008 and the improvement follows substantial investment in new cranes, expansion of its yards and the development of a port community system, with much improved rail and road connectivity with the hinterland and neighbouring Mali.

Maritime transport moves over 80% of global trade by volume. Container ports form the backbone of this system.

The report shows those ports with rising CPPI scores have often pursued digitalisation along with 24/7 operations and streamlined coordination with customs and logistics partners.

ALSO READ: Academic heavyweights line up on either side in Durban container port case

The graph below shows sub-Saharan Africa (in red) – of which SA ports form a major part – lagging the rest of the world by a considerable margin.

Some analysts, such as Ryan Hawthorne, a director at Acacia Economics and a leading expert in competition and regulatory policy, have argued that Transnet National Ports Authority’s (TNPA) policy of pursuing long-term concessions – often with a single operator in joint ventures with other Transnet divisions – risks replacing public monopolies with private ones and may miss the opportunity to build a more competitive and efficient port system.

The TNPA is still legally part of Transnet and has awarded a number of multi-year leases to single terminal operators, often involving Transnet Port Terminals as a joint venture partner.

Hawthorne, speaking at the recent Southern African Transport Conference, advocates a return to inter-port rivalry, as existed more than a century ago, when Durban and Cape Town actively competed for shipping traffic.

Durban is expected to expand its container-handling capacity to more than 11 million TEUs – enough for multiple competing operators.

“Ports of similar size internationally to Durban’s current capacity host four or more terminal operators competing on quality and cost,” he explains. “There’s no reason South Africa can’t follow suit,” said Hawthorne.

* Transnet is yet to comment on the World Bank’s latest report. Moneyweb has reached out to Transnet and this story will be updated once a response is received.

This article was republished from Moneyweb. Read the original here.