Less Ho-Ho-Ho, more No-No-No for SA consumers in festive season

Myanmar’s military is accused of waging an ethnic cleansing campaign against the stateless Muslim minority, more than 600,000 of whom have fled a crackdown in northern Rakhine State for neighbouring Bangladesh over the past three months.

Francis will meet powerful army chief Min Aung Hlaing during the trip in a highly anticipated encounter between a religious leader who has championed the rights of refugees and the man accused of overseeing the charge to drive out the Rohingya.

He will also meet civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi — a Nobel laureate whose international standing as a moral icon has crumbled over what the world sees as her lack of sympathy for the Rohingya.

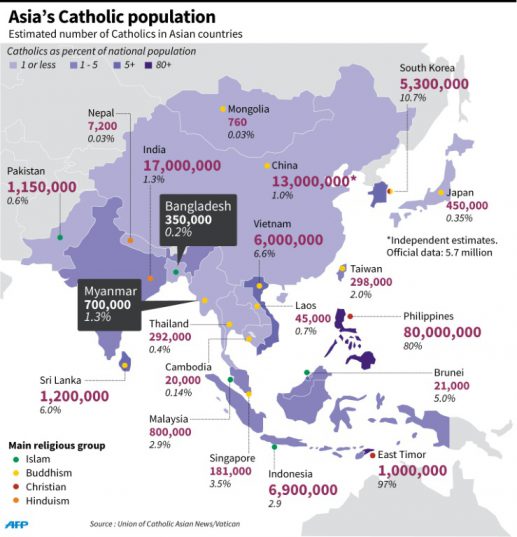

Myanmar’s 700,000 Catholics — just over one percent of the country’s 51 million people — generally enjoy good relations with their mainly Buddhist compatriots and are gripped with excitement over the first ever papal visit.

“As I prepare to visit Myanmar and Bangladesh, I wish to send a message of greeting and friendship to everyone. I can’t wait to meet you!” Francis said in a message posted on his official Twitter account ahead of his trip, which will also see him visit Dhaka.

Pope Francis previously met Aung San Suu Kyi in Vatican City in 2013 and called for inter-religious dialogue in Myanmar

Speaking to a crowd of 30,000 people in St Peter’s Square, shortly before he left Rome, the pontiff said: “I ask you to be with me in prayer so that, for these peoples, my presence is a sign of affinity and hope”.

The pope has been forthright about his sympathy for the Rohingya from afar, calling them “brothers and sisters” and deploring the plight of hundreds of thousands of children swept up in the violence.

But the country is holding its breath over what the pontiff will say on Myanmar soil, where any mention of the word Rohingya could unleash anger from a public that broadly supports the army campaign.

Many in the Buddhist-majority nation view do not view the minority as indigenous — referring to them as “Bengalis” — and view them with hostility.

“The vast majority of people in Myanmar do not believe the international narrative of abuse against the Rohingya and the refugee numbers that we’re seeing in Bangladesh,” said Myanmar-based political analyst Richard Horsey.

“If the pope did come and weigh in heavily on this issue, it would inflame tensions and it would inflame public sentiment,” he added.

– Prayers for peace –

Asia’s Catholic population

Myanmar’s army, which ran the country with an iron fist for nearly half a century, insists its Rakhine operation was a proportionate response to Rohingya “terrorists” who raided police posts in late August, killing at least a dozen officers.

But rights groups, the UN and the US have accused the army of using its reprisal as cover to violently expel a minority it has oppressed for decades.

Days before the pope’s visit, Myanmar and Bangladesh inked a deal vowing to begin repatriating Rohingya refugees in two months.

But details of the agreement — including the use of temporary shelters for returnees, many of whose homes have been burned to the ground — raise questions for Rohingya fearful of coming back without guarantees of basic rights.

Myanmar’s around 700,000 Catholics — just over one percent of the country’s 51 million people — generally enjoy good relations with their mainly Buddhist compatriots and are gripped with excitement over the first ever papal visit

Many of Myanmar’s Catholics are travelling from other conflict-weary corners of Myanmar to join a huge, open-air mass led by the pope on Wednesday in the economic hub, Yangon.

Stepping down from a train in the city’s bustling main station, Hla Rein said he had made the long journey from the northernmost state of Kachin with high expectations.

“There is a civil war in our state,” he told AFP, referring to a separate long-running conflict between Kachin rebels and government forces.

“We believe that the Pope will bring peace with him to our country.”

Download our app and read this and other great stories on the move. Available for Android and iOS.