Secret Steinhoff PwC report to be handed over on Wednesday to some media

Making it big, even leaving Kibera: these weren’t things that happened to an orphan who once robbed people to buy food.

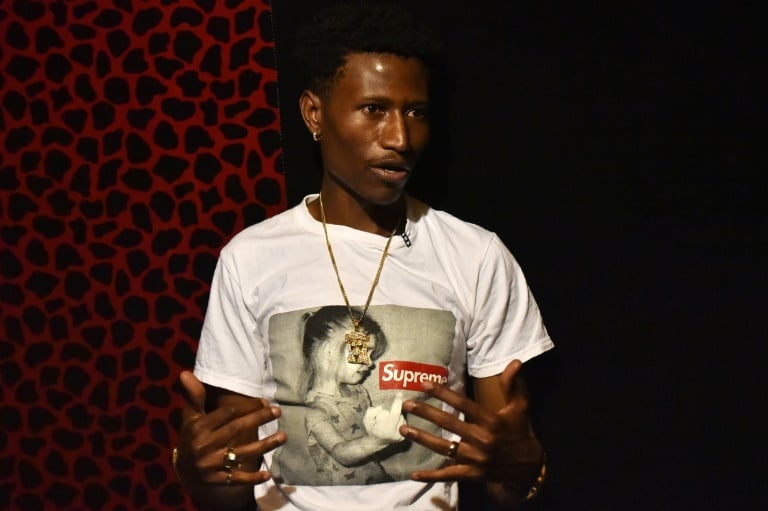

Now 29, he is Octopizzo, one of East Africa’s most recognised hip-hop stars, and is using his success to break down stigma around the slum and inspire kids in a world devoid of successful role models.

Clad in a black Adidas tracksuit, with bling in his ears, a gold-coloured watch on his arm and a large dazzling pendant of Jesus around his neck, Ohanga gestures over the undulating hodge-podge of corrugated iron roofs where he grew up.

“It’s everything, everything I rap about… I feel like if I wasn’t born here I probably wouldn’t be a rapper,” he told AFP in Kibera, where most of his friends and family still live.

Octopizzo is one of East Africa’s most recognised hip-hop stars

Kibera stretches over an area of about 2.5 square kilometres (one square mile), a poor ethnic melting pot wedged among richer areas of the Kenyan capital where its residents work, mostly as casual labourers.

The slum’s population is subject to heated debate, with the old NGO slogan of “the biggest slum in Africa” challenged in recent years by a government census and other independent studies which say between 170,000 and 250,000 people live there.

While for some a byword for misery and poverty, to Octopizzo, Kibera is the place he loves “more than anything else in the world” and it features in every one of his hits, with some of his slick, foreign-produced videos racking up more than a million views on Youtube.

In Kibera it is not the rubbish packed into dirt or debris-choked streams that strike Ohanga.

Rather he is inspired by the “uniquely beautiful vibe”, children in brightly coloured uniforms making their way to school, music blaring from speakers around every corner, the whirr of sewing machines set-up in open air, the rhythm and beat of the hustle.

“I don’t blame the people. If you look at Kibera this is the definition of a failed system,” he said.

– ‘Changing the narrative’ –

Octopizzo is inspired by the “uniquely beautiful vibe” of the Kibera slum

While he describes himself as more “socially conscious” than political, it has been hard to avoid tough topics in the slum, which is often the first place sparks fly when political tensions rise.

During Kenya’s 2007 post-election crisis, when he recalls having to walk everywhere with a machete for protection as the slum was torn apart by ethnic violence he blames on politicians, his anger spilled into his first recorded song: “Voices of Kibera”.

However his big commercial break only came in 2012, through an arts programme at the British Council, which launched other successful artists such as afro-pop band Sauti Sol.

Ohanga has moved on to rapping about things like food and fashion from Kibera, to change the negative image of the slum that has long led those who do make it out to hide their roots.

“I feel since I started rapping we have changed the narrative, it is cool now to be from Kibera.”

But politics and Kibera remain deeply intertwined, and when post-election protests broke out last year, Ohanga came to the slum to speak to both protesters and police, and criticised police violence that left scores dead in Kenya, including residents of the slum.

“I have a voice and I have to use it, whether people like it or not,” he said.

– ‘The face of possibility’ –

Octopizzo says of the Kibera slum: “If I wasn’t born here I probably wouldn’t be a rapper”

Ohanga had never planned to become a rapper — growing up he wanted to be a horticulturalist. “I like flowers,” he said.

But the opportunity never came his way. His father died when he was 14, his mother a year later, and he ended up living with a friend and joining a gang, robbing shops and people.

“I never regret being part of that, I never killed anybody,” said Ohanga, who has an entire song dedicated to gangsters and drug dealers — the only ones to help him when he was down and out.

Through his own foundation, and work with the UN refugee agency, he wants to help youths realise their potential through the arts.

In 2016, artists from the Kakuma and Dadaab refugee camps who were trained and mentored by Ohanga released an album called “Refugeenius”.

“I want to be the face of possibility. When we grew up we didn’t know anyone who was successful. Kids are told by their teachers, their parents that they will never be anything, it is not our destiny,” said Ohanga.

One young man he has inspired is 22-year-old Daniel Owino, who Ohanga described as a “bad kid” in trouble with everyone in the neighbourhood.

“I told him: ‘Even me I used to be there, we’ve robbed guys it’s not a big deal but we change’,” said Ohanga.

Owino, now known as Futwax, turned his life around, and is working as a motorbike taxi driver as he pursues his passion for music, with 13 songs recorded so far. He was also recently crowned Mr Kibera.

“He is a role model to me. I used to go to his house here in the slum, Octopizzo was so hardworking. I felt that even I would make it one day,” Owino told AFP.

Download our app and read this and other great stories on the move. Available for Android and iOS.