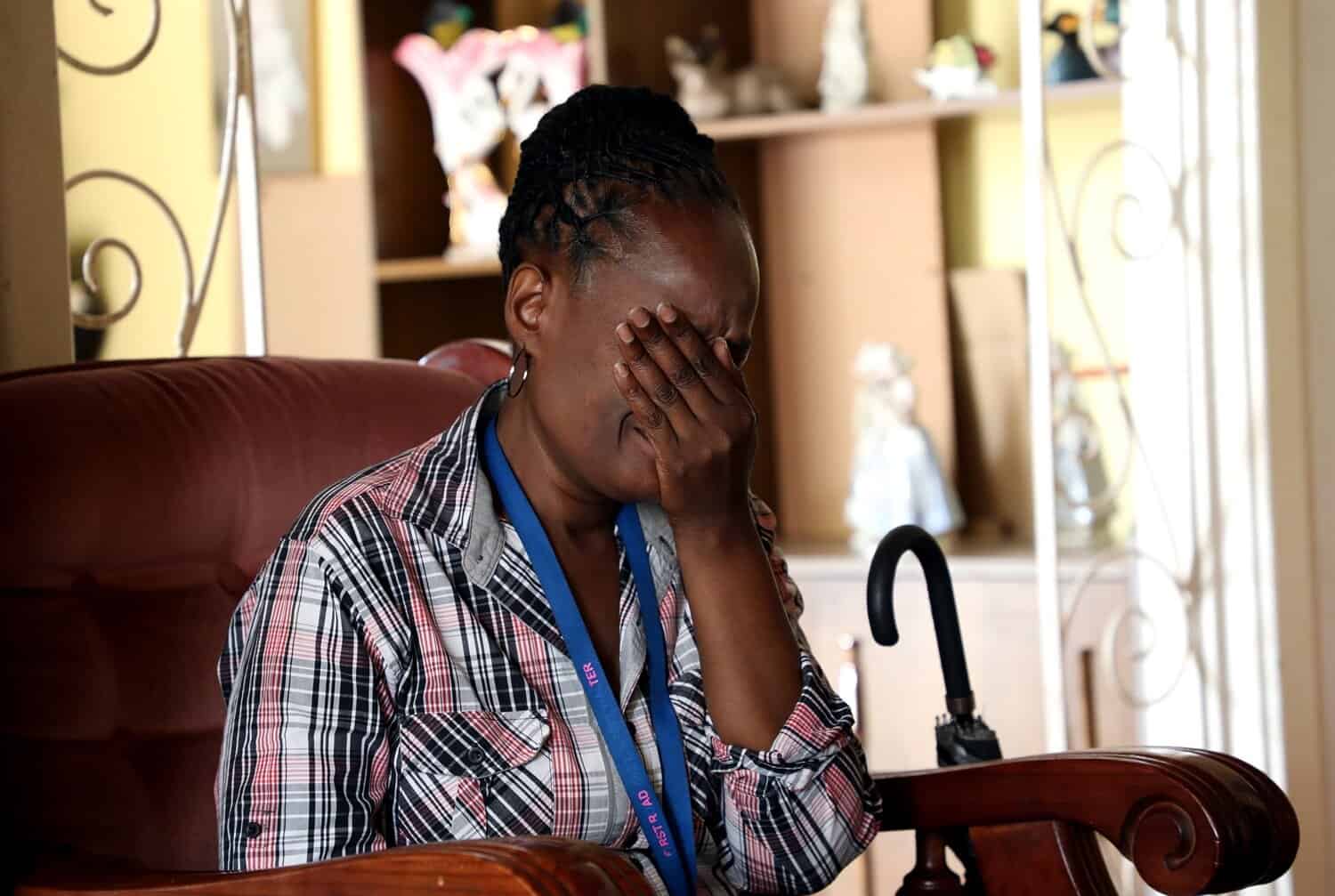

Women in South Africa face abuse in labour wards, from non-consensual procedures to neglect, highlighting systemic failures in maternal care.

When Tasneem, not her real name opened her eyes, gradually regaining consciousness, she was abruptly told to get up.

But when she tried to stand, she saw blood everywhere – her back, hair and mattress were soaked. When she finally stood up, the blood had pooled across the cold, tiled floor.

Although the description of her ordeal bears the hallmarks of harrowing stories of rape and femicide in South Africa, Tasneem wasn’t beaten by her partner or attacked by a stranger.

Still, what happened to Tasneem is gender-based violence (GBV), albeit in a lesser-known form, called obstetric violence.

During labour at her local hospital, Tasneem was subjected to forced dilation and induction; her amniotic sac was broken without consent. The pain caused her to black out.

ALSO READ: Is there justice for women forcibly sterilised?

In theatre, forceps were used to deliver her baby, injuring her newborn so severely that the little one needed surgery.

Her story is not unique. While labour wards are stressful places and life-threatening obstetric events often necessitate urgent intervention, the rights and dignity of women in labour are frequently disregarded.

Unlike domestic violence or sexual assault – widely recognised as criminal or social harms – obstetric violence is often treated as a medical issue. Not a gendered violation.

While we don’t yet have national prevalence data on obstetric violence in South Africa, a systemic review of 25 global studies over 10 years found the prevalence of obstetric violence to be 59%, with non-consensual medical care emerging as the most common violation.

Obstetric violence covers overt acts of harm like hitting, pinching and restraining someone in labour; it also includes subtle violations such as neglect, verbal abuse, denial of privacy or reproductive health care and performing procedures without informed consent.

ALSO READ: Battle over pregnancy grants ignores what babies need most

Like other forms of GBV, violence in health care is underpinned by systemic power imbalances, deeply entrenched patriarchal norms and a culture that does not value women’s bodily autonomy.

Obstetric violence is also embedded in structural failings – overcrowded hospital wards, chronically understaffed facilities and underresourced hospitals, where dignity is sacrificed.

A scholar, Jess Rucell, says that SA’s history of colonialism and apartheid continues to influence how health care workers deliver maternity care today.

In addition, Sue Gray from the University of KwaZulu-Natal argues that obstetric violence is “health care paternalism”, reflected in patriarchal attitudes held by health care workers.

A recent survey by Embrace on women’s birth experiences revealed that obstetric violence has profound consequences for women – physical complications, long-term psychological trauma and an enduring mistrust of SA’s health care system.

ALSO READ: Proposed policy aims to extend child support grant to pregnant women

Still, obstetric violence tends to be dismissed as “routine care” or “medically necessary”, thereby diminishing its profound harm.

An ethnographic study in an obstetric unit at a community health care facility in rural KwaZulu-Natal highlighted how undignified maternity care is normalised, with health care providers preventing women – especially teenagers – from taking decisions about their own health and care.

They were subjected to procedures without consent, physical or verbal abuse, or were withheld pain medication.

The same study showed that some women accepted physical abuse as normal, going so far as thanking their midwives for the rough handling, believing it necessary for safe delivery. The midwives reinforced this view.

Last year, the national department of health updated its integrated maternal and perinatal care guidelines and for the first time included a dedicated chapter on respectful maternity care.

ALSO READ: Mother of seven to appear in court for concealment of birth

The department acknowledges that respectful maternity care is not only essential for improving patient experiences and clinical outcomes but necessary for health worker morale, job satisfaction and upholding the dignity and standing of the profession.

Such training does help to improve the experience of patients. There are a handful of studies across the continent that demonstrate when health care workers are supported, trained and given tools to reflect on their practice, respectful maternity care is achievable and scalable.

In Tshwane, the Clever maternity care pilot showed significant improvements in women’s experiences of dignity, communication and overall satisfaction after midwives received a combined package of clinical support, feedback systems and respectful care training.

At the second presidential summit on gender-based violence and femicide in 2022, Embrace and other civil society partners successfully lobbied for obstetric violence to be recognised as a form of GBVF, including forced and coerced sterilisation.

Respectful maternity care cannot be optional or conditional, it must be systematically embedded.

NOW READ: Health department cites confidentiality in C-Section controversy

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.