The department of human settlements' register has 3.8 million households awaiting homes, some for over 20 years.

The pace at which government-subsidised housing is being built has slowed to half of what it was a decade ago.

For the government to provide homes for all those on the national waiting list, it would have to build almost four times the number of houses it has already done since 2011.

However, the department of human settlements (DHS) said that rising construction costs and slow economic growth would likely see the continuation of the slow progress.

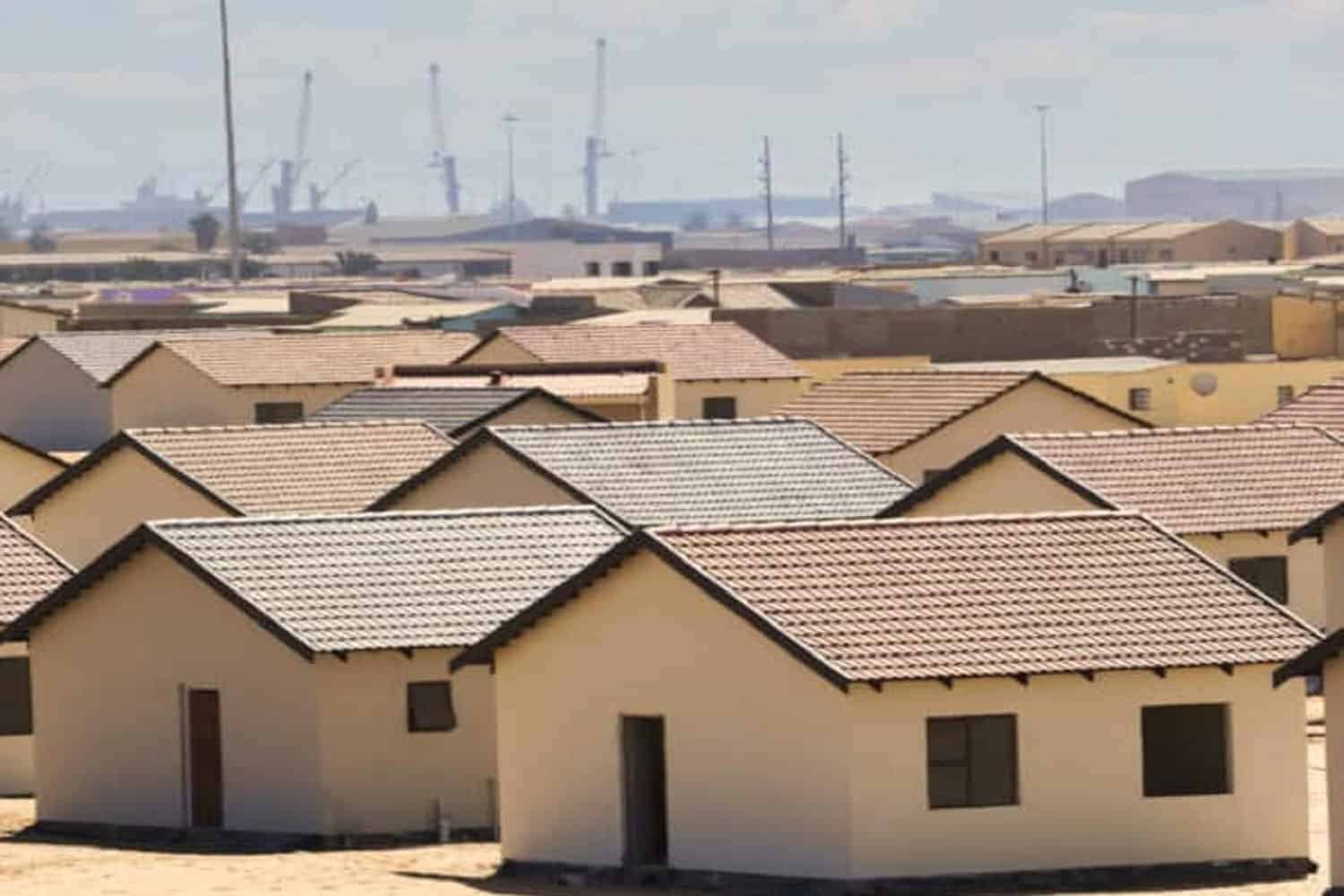

3.2 million RDP houses since 1994

DHS has provided roughly five million housing opportunities since 1994, consisting of 3.2 million RDP homes, 1.3 million serviced stands and roughly 490 000 hostel or rental units.

Considering brick and mortar sites only, annual state-subsidised housing construction peaked in 1999 with 235 635 units built that financial year

From 2001 to 2010, government housing output averaged between 120 000 and 160 000 per year, but has falled almost every year since and last exceeded 100 000 in 2015-16.

In the 2024-25 financial year, only 38 453 housing units were completed, with that figure last breaching 50 000 in 2019-20.

According to DHS’ response to a written parliamentary question submitted in October, the department’s output for the current financial year could fall just short of the 20 000 mark.

3.8 million households waiting

While roughly 1 million homes were built since 2011, 1.2 million households have registered for government housing in the last five years.

The department measures households at having an estimated occupancy of 3.5 persons.

Additionally, a further 1.1 million households have registered for housing in the last five to 10 years.

The wait times for thousands of recipients exceed a decade, with DHS confirming that 860 604 households had been on the waiting list for 10 years or more.

Alarmingly, 587 328 households had spent 20 years or more on the waiting list, as per DHS’ October response.

The department clarified that it did not have a national housing database, but a National Housing Needs Register, which listed 3.8 million household awaiting housing allocations.

Slow economic progress

A white paper on human settlements published earlier this year said that housing programmes had been affected by the high cost of building materials, the cost of transactions, taxes and professional fees.

“The cost of providing housing increased greater than in proportion to the increases in subsidies, leading to fewer state housing units being provided,” the white paper said.

“The economy has faced a series of global and local disruptions, including slowing global growth, geopolitical tensions and wars and the Covid-19 pandemic among others,” it added.

DHS noted how South Africa’s economic growth had averaged 3.6% during the years of high housing output and how it had slumped to under 1% in recent years.

“[This is] lower than that of upper-middle income countries and sub-Saharan Africa on average. This highlights that the South African GDP is projected to continue to stagnate,” the white paper said.

To secure funding, the white paper suggests approaching capital markets, providing “incentives for those who donate land” and increased taxation.

“DHS will pursue a trajectory and enhance a notion whose noble intention is to advocate for its programmes to be zero-rated to enhance affordability.

“A regulation that provides certainty will be issued by the minister of human settlements in consultation with the minister of finance,” the white paper said.

NOW READ: Gauteng’s housing crisis: 150 years to clear the backlog

Support Local Journalism

Add The Citizen as a Preferred Source on Google and follow us on Google News to see more of our trusted reporting in Google News and Top Stories.