Beverage industry starts to freeze jobs and investments as sugar tax looms

As it counts the cost of government’s ambitions to trim bellies and fat.

After spotting a quality controller vacancy online at bottling and distributing company Coca-Cola Peninsula Beverages in July, Steven (not his real name) thought the job offer was right up his alley.

One or two years’ experience in general lab work. Tick. A science-related tertiary qualification. Tick. The willingness to relocate to the Western Cape where the company is headquartered. And tick.

Believing he was “over-qualified” for the job, the Gauteng-based applicant proceeded to apply.

Two months later, he received an unusual response from the prospective employer – the quality controller and all vacancies at Coca-Cola Peninsula Beverages were cancelled due to the pending tax on sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs).

“Once we have clarity on the way forward, we will reassess our vacant positions and approved positions will then be recruited for,” the company said in response to Steven’s application.

This may be a sign of things to come in the beverage industry if the National Treasury forges ahead with a tax on sugar beverages in April 2017.

Already the Durban-based SoftBev, which is a small to medium bottler for PepsiCo products in South Africa and other low-cost brands such as Jive, 7 Up and Coo-ee, put an expansion investment of R100 million on hold last month due to the uncertainty of the proposed tax.

SoftBev CEO Brett Naidoo said the company will “wait on the investment until we have a proper understanding of the tax.”

South Africa will be joining countries such as Mexico and Mauritius that have taxes on SSBs, with the government proposing a levy of R2.29 per gram of sugar on beverages or a 20% tax rate.

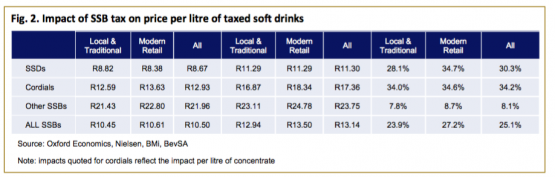

See price changes of beverages below at different retailers below:

screen-shot-2016-09-29-at-3-45-35-pm

Glossary:

Cordials: squashes, cordials, powders and other concentrates for dilution to taste by consumers.

SSBs: beverages that contain added caloric sweeteners such as sucrose, high-fructose corn syrup, or fruit juice concentrates.

SSDs: sugar-sweetened drinks, including colas, mixers, and flavoured carbonated drinks.

Source: Oxford Economics.

The beverage industry has argued that between 60 000 and 70 000 jobs might be on the line across the entire value-chain including farmers, bottlers, manufacturers, distributors and retailers (large chains and informal spaza stores).

An Oxford Economics issue paper that assesses the economic impact of the SSB tax predicts that sales volumes of soft drinks will decline by 25.6%, as consumers will switch away from taxed products to those which will not be subjected to the tax levy such as pure fruit juices and milk.

Also, SSB sales volumes are expected to decline by 33% as beverages will be more than 20% costly. The Oxford Economics paper that was released last week uses contributions and data from soft drinks companies as its methodology.

According to the paper, the soft drinks industry contributed R59.7 billion to South Africa’s GDP in 2015 and supports up to 306 500 jobs across the value chain. An SSB tax will decrease the industry’s contribution to GDP by R14.6 billion.

The beverage industry is now on tenterhooks. Coca-Cola Peninsula Beverages, which is the local bottler and distributor of The Coca-Cola Company beverages in the Western and Northern Cape, is preparing for the unforeseen consequence of the tax.

The company’s spokesperson Priscilla Urquhart said only indirect jobs related to its operations might be cut and not permanent jobs. Coca-Cola Peninsula Beverage employs currently employs 1 350 people.

“In our 76-year history, we have never retrenched a single person and hopefully we will never have to find ourselves in a position where we retrench people. We will adjust to make sure that no one’s employment in the business is affected,” she said.

Treasury hits back

The National Treasury has not minced its words on the job losses that the beverage industry raised – labelling its actions as “scare-mongering”.

Treasury’s deputy director-general for tax and financial sector policy Ismail Momoniat said the burden and cost of obesity have been carried by the public sector while beverages companies have not been affected.

“Their response indicates how they haven’t clearly understood the signs [of an obesity problem] and resort to such tactics, which means that they undermine the public debate on this matter,” Momoniat told Moneyweb.

In its policy paper that was published in July for public comment, the National Treasury noted that obesity rates have grown in the past 30 years, with over half of the country’s adults being obese. That is about 42% of women and 13% of men who are deemed obese.

Beverages that don’t have proper nutritional labelling will pay a higher tax as they are automatically classified to have a high sugar content. In 2002, a tax was imposed for revenue purposes but was later phased out after lobby efforts by the industry.

Although the National Treasury has not estimated the revenue that it will raise from the tax, industry estimates have pegged an amount of between R7 billion to R11 billion that will be added to the fiscus in year one.

The big question then is why isn’t the government ring-fencing the revenue collected to be deployed on obesity-combating initiatives instead of, for example, using the revenue to bankroll the country’s costly foray into nuclear energy.

Said Momoniat: “Ring-fencing taxes is a dangerous way to go. You can’t do that in a tax system to say that this particular amount of tax is going to health or elsewhere. That would undermine the transparency and could also mean that the right amounts cannot be allocated.”

The government believes that the tax might be a catalyst for behavioural changes. It cites a report by Wits University researchers Mercy Manyema, Karen Hofman and others, which showed that a 20% tax on SSBs will reduce obesity in South Africa by 3.8% among men and by 2.4% among women equivalent to more than 220 000 less obese adults.

The industry has dismissed the obesity reduction claims as it foresees consumers substituting to taxed beverages to tea and coffee, which can be sweetened to their desires.

Beverage industry punked

The chairperson of Beverage Association of South Africa and MD at Coca-Cola Beverages South Africa (CCBSA) Velaphi Ratshefola said over the past two years, the industry has worked with the Department of Health to lower the consumption of sugar before the tax even surfaced.

Of the 3 000 calories people are consuming per day, Ratshefola said sugar makes up 10%, while five years ago, it was 12%. “Sweetened beverages make up only 3% of the calories. The sugar tax is discriminatory despite the declining sugar intake. Of all the calories, the government chooses one component. What about salt, saturated fats and others?” he asked.

Ratshefola said the industry had already reformulated its beverages by reducing added sugar, promoted detailed nutritional labelling on beverages and introduced smaller package sizes in addition to king size beverages. These initiatives, he said, could reduce the average daily energy intake by at least 14 to 18 calories by 2020 – which is double the estimated target of 7 to 9 calories by the National Treasury.

Measures specific to CCBSA include increasing the availability and marketing of low-and no-calorie options such as Coke Light and Coke Zero. Coca-Cola Life, which substitutes sugar for stevia, a plant sweetener, was recently introduced to the range of options. Changes also followed on its marketing strategy: C0ca-Cola stopped advertising to children under the age of 12.

Arguably, a beverage company like CCBSA can absorb volume sale losses given its juggernaut operations than emerging and small counters.

Little Green Beverages, which is a small manufacturer and distributor of flavoured soft drinks to retail outlets such as spaza shops, is already forecasting that 13 000 small outlets will shut their doors as a result of the sugar tax. Director of Little Green Beverages Glenn Sheppard said the drop in sales volume of SSBs will hit their profit as they generally don’t stock a wide range of soft drinks.

“They don’t have the capacity to employ additional people to run those spaza shops. If the volumes drop down by 35%, those businesses will close because it’s absolutely not sustainable,” said Sheppard.

Although Little Green Beverages is not freezing jobs, Sheppard said the tax makes it difficult to make new capacity expansion investments such as machinery when factoring potential volume sale losses of SSBs.

-Brought to you by Moneyweb