‘Malema has created a militant style of leadership in the EFF’

“A strange and grotesque specimen of bird… bearing a ridiculous bent bill,” was the verdict of early 17th century Dutch admiral and explorer Wybrand van Warwijck.

Subsequent expeditions of sailors feasted on the helpless fowl even as they disparaged the flavour of its flesh as “the devil’s chicken”.

By 1680, the dodo — found only on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius — was extinct, wiped out by human appetites and invasive species brought by settlers.

So deep was our contempt for this hapless creature that during a century of co-habitation no one bothered to closely observe its habits, or accurately describe its anatomy.

And then, it was too late.

Adding insult to injury, early scientists dubbed the dodo “Raphus cucullatus,” and decided that it belonged to the same family as the lowly pigeon.

It’s informal name may be derived from the Dutch term “dodoor”, which mean sluggard. Another candidate is “dodaers”, which translates as “plump arse”.

Perhaps both.

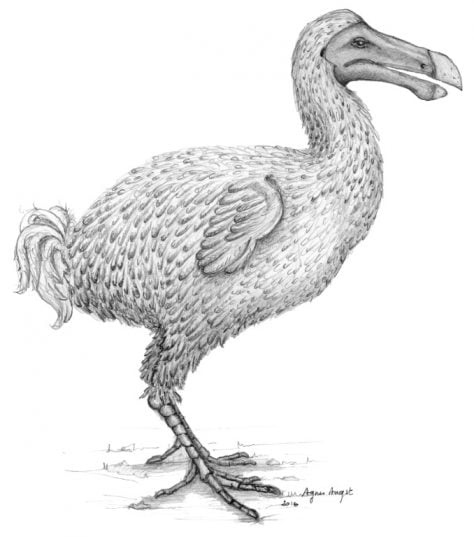

A reconstruction of the extinct dodo bird, in a handout photo released by Nature

“The dodo is frequently described as a stupid, fat bird,” said Delphine Angst, a biologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa.

“But truth be told, we know almost nothing about it.”

In a study published Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports, lead author Angst and colleagues from the Natural History Museum in London make important headway in filling that knowledge void.

Using techniques that would impress Sherlock Holmes, they mapped out the animal’s reproductive and growth cycle.

– Battered by storms –

Females dodos, they determined, ovulated in August, during the southern hemisphere winter, laying eggs that hatched in September.

“The chicks grew very quickly to be strong enough to endure the austral summer, which is the season of cyclones and storms on Mauritius,” Angst told AFP.

At the end of summer around March, young dodos would start to moult, loosing their birthday suits — battered by the storms — and growing adult feathers.

“By the end of July, all the feathers would have been renewed and the period of reproduction could start,” said Angst.

Dodos probably weighed 10 to 14 kilos (22 to 30 pounds), she added.

How did Angst and her colleagues figure all this out?

But analysing the microscopic structure of crushed dodo bones.

The technique, called histology, is not new but had never been applied to the world’s most famous flightless bird.

“Histology has been around for decades, but the method is a destructive and could not — up to now — be applied to dodo fossils,” explained Angst.

Somehow, Angst and her colleagues managed to convince museum curators around the world to donate samples for the study.

In the end, they had 22 bones from 22 different dodos to work with.

The bird’s courtship and mating rituals, however, are still a mystery, and may always remain so.

Download our app and read this and other great stories on the move. Available for Android and iOS.