For down-at-luck Brazilian football club, dreams live on

Tiny Sao Cristovao Football Club gave Ronaldo "the Phenomenon" his start and a quarter century later manager Antonio Carlos Dias hasn't given up dreaming that he might discover Brazil's next superstar.

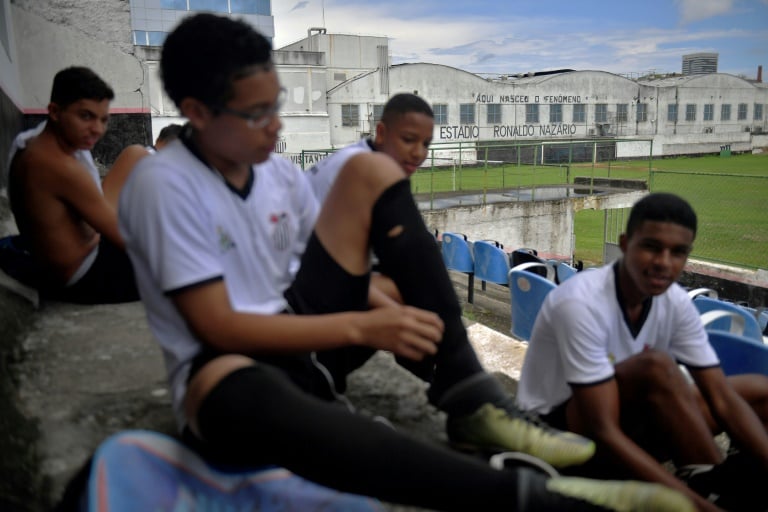

Viewed from the club’s weatherbeaten grandstand in a gritty part of Rio de Janeiro, Dias’ ambition might sound far-fetched.

Yes, Ronaldo became one of the world’s best footballers. But he last played for Sao Cristovao as a teenager back in the early 1990s, and the club has been on the skids ever since.

Huge letters behind one of the goals read: “The Phenomenon was born here.”

The reality is a bumpy pitch, a clubhouse badly in need of paint and a team stuck in Rio state’s third division.

Still, this is Brazil. This is the country of Pele, Zico, Socrates, Kaka and all the talent assembling for this summer’s World Cup in Russia — Neymar, Gabriel Jesus and company.

This is a country where even lowly Sao Cristovao can dream.

“We have a lot of stars in Brazil,” Dias said, as he watched the club’s class of 12-14 year old academy boys play fast passes over the ragged grass. “The potential supply is bottomless.”

– ‘Born with it’ –

Like their footballing heroes, nearly all the kids learning at Sao Cristovao are from favelas, the tight-knit, poor and often violent Rio neighbourhoods where sport is a rare escape.

“Some are lost due to the environment around them — to drug trafficking, to easy money,” Dias said. Many arrive at training not having eaten properly.

The club takes them under its wing. Then “we start fishing for the one who might make it,” Dias said.

Brazil’s 2002 World Cup-winning striker Ronaldo hailed from the same poverty-stricken background as the boys at the club

Ronaldo himself was born poor in Rio, going on to score 62 international goals, win two World Cups, and stun opponents with his high-speed dribbling at PSV, Barcelona and Inter Milan.

The boys running about on Sao Cristovao’s field today still love him.

“I want to be like Neymar or Ronaldo, to make the national team of Brazil,” said Mauricio Almeida, 15, wearing a Sao Cristovao academy shirt with the slogan “Factory of the Phenomenon.”

Youth coach Renato Campos, 56, remembers Ronaldo standing out as a gap-toothed teen, but says there’s nothing easy about picking a future champion. “You wouldn’t have said he’d be the best player in the world.”

Then the coach’s eye roved over the pitch, as if somewhere on that patchy grass a new “Fenomeno” might blossom. He fixed upon an undersized but skilful boy who consistently beat bigger defenders.

The boy will be “practically hopeless” on the international market, Campos said in a matter of fact way, but “will do well here in Brazil.”

“You see the difference in the quality of how they strike the ball, the quality of their passes, their determination,” Campos said.

“Some you have to work with them on this. Others are born with it.”

– Meaning of football? ‘Everything’ –

Brazil’s ability to produce footballing genius may look effortless. The truth is that the sport, like so many things in Latin America’s biggest country, is held back by poor financing and corruption.

Sao Cristovao, one of Rio’s best clubs back in the early 20th century, is a perfect example.

The trophy room is an Aladdin’s Cave of gleaming silver and gold cups, but they mostly celebrate the footballing equivalent of ancient history.

The young players at the Sao Cristovao club come are from favelas, the tight-knit, poor and often violent Rio neighborhoods where sport is a rare escape

Ronaldo’s fading connection to the club is even more poignant: on the club notice board — which has no recent notices — appears a fading photograph of the last time the star visited. It’s dated January 2014.

Dias says years of financial mismanagement rather than lack of talent ruined Sao Cristoval. Those same “dark” practices also scared Ronaldo off coming back to lend his boyhood club a hand.

But Dias, 49, believes he can restore the club “to its past glory” and demonstrate to investors — and hopefully Ronaldo — that the club is now “free of corruption.”

A former professional footballer in Brazil and Portugal, Dias took over Sao Cristovao just three months ago. He has poured in his own money, changed key staff, bought new kit, and is targeting promotion to the second division, with an eye on the first division in 2020.

“Sometimes my family tells me that I sound crazy,” he laughed, but “I love this club and I love football.”

Or, as 14-year-old trainee Jorge Gabriel replied when asked what battered, but brave Sao Cristovao meant to him:

“Everything.”

For more news your way

Download our app and read this and other great stories on the move. Available for Android and iOS.